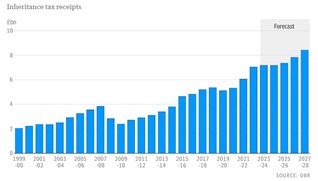

“More than 93% of estates aren't expected to pay any inheritance tax in the coming years — however, the tax still raises more than £7 billion a year to help fund public services like the NHS and schools.”

HM Treasury spokesman

A vigorous debate has opened up about the merits or otherwise of inheritance tax. The Conservative Growth Group is leading a campaign for its abolition, and former Chancellor of the Exchequer Nadhim Zahawi has put forward a strong case for that in his article in last Wednesday's Daily Telegraph.

Naturally HM Treasury attempted to justify its continuation in the quotation above in The Times the following day: but the last part of that quotation shows that they totally misunderstand the difference between applying levies on long-term private capital and taxing current income and expenditure.

It's what the levy is used for that matters, and funding ‘public services like the NHS and schools’ steals assets built up for tomorrow for subsidising today's expenses.

Inheritance tax needs to be reformed, not abolished, but its purpose needs to be properly defined and its distortions must be addressed.

Defining its purpose

Let's start with the opening sentence of Nadhim Zahawi's article: ‘The most natural feeling in the world for any parent is to want to look after their children. This feeling is so powerful that it stays with us until our last breath, and even beyond; we all want to leave the world a better place for those who follow us, and leaving behind what we have built and earned in life is a crucial part of that.’

Nadhim is speaking in the context of his own family, but I would invite him and others to think in terms of the whole human family: because, as he says: ‘We all want to leave the world a better place for those who follow us’. That wish should not be restricted just to our own direct descendants.

In the late 1980s, I wrote to Margaret Thatcher putting forward a proposal for ‘Popular Inheritance’: here's a version of it, updated in 2004. I received a substantive reply from her, but no action was taken by HM Treasury at the time.

In the late 1990s following the change of Government, I wrote to Gordon Brown, re-naming my proposal ‘Youth Legacy’, and a few years later the Child Trust Fund was announced. However, there was still no direct linkage drawn between inheritance tax receipts and what they finance. On repeated occasions I have written to HM Treasury calling for inheritance tax to be hypothecated for inter-generational rebalancing, and each time my request has been turned down.

If Nadhim Zahawi and his colleagues accept that the purpose of applying an inheritance levy is to provide an individual inheritance for young people who have no prospect of receiving such support from their own natural family, there would be no good reason to call for its abolition, since it would no longer be squandering privately-owned capital by absorbing it into current public expenditure. As a former Children's Minister in the Department for Education, I am sure he understands the rationale for funding inter-generational rebalancing in this way.

Reforming its application

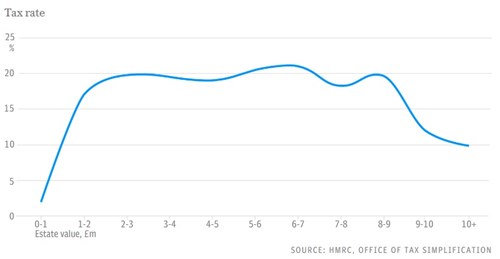

However The Telegraph article on 2nd June, following Nadhim Zahawi’s commentary, is right to call for reform of the tax. It included a chart showing how the highest effective tax rate only applies for estates valued at between £2 million and £9 million: above that level, the various exemptions — many of which are well-justified — are used to reduce that effective rate by half:

It's hard to argue against the various exemptions that apply, particularly those which are designed to ensure that entrepreneurial and long-standing family businesses are not put at risk by enforced disposal. This includes AIM and unlisted shares and agricultural property relief. Gifts to charity should likewise continue to be exempt.

Reform should therefore involve a careful review of the thresholds at which inheritance tax applies, which are undoubtedly too low at present and result in too many estates being dragged into the tax — and adjusting the rate itself, perhaps on a tiered basis starting at 20% and rising in stages to the current level of 40%. The objective should be to restrict the application of inheritance levies to those estate values of at least £5 million or more at the point of death, and to flatten the effective tax rate to 10% above this level.

This reform may lead to a significant reduction in the amount raised, which is currently over £7 billion per annum (having almost tripled over the past ten years). However its new closely-defined purpose as proposed earlier, to provide starter capital accounts and life skills for young people with no prospect of receiving such support otherwise, could be met with an annual allocation of c. £2 billion per annum.

This reform may lead to a significant reduction in the amount raised, which is currently over £7 billion per annum (having almost tripled over the past ten years). However its new closely-defined purpose as proposed earlier, to provide starter capital accounts and life skills for young people with no prospect of receiving such support otherwise, could be met with an annual allocation of c. £2 billion per annum.

And how would the £7 billion hole in general taxation be filled? The logical approach would be for wealthy old folk to pay for their own health service needs through mandatory health insurance, as we proposed on 17th October last year.

Finally, it's worth recalling the application of inheritance taxation overseas by re-visiting the OECD booklet prepared in 2021. This shows the incoherent nature of inheritance levies across the world and indicates that, just as in the United Kingdom, the proceeds are more often than not squandered on current public expenditure. Establishing a clear purpose for the inheritance levy and reforming its application here in the United Kingdom should therefore set a helpful example for global inter-generational rebalancing, a strong step forward towards introducing a more egalitarian form of capitalism.

It’s also an appropriate recognition of the natural human cycle of life and death, and of course the fact that we can't take it with us when we die.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio