In a world where the two dominant economic systems have been shaped by their impact on individuals, I am always surprised that the study and disciplines of economics are always driven by aggregates.

Those two dominant economic systems are, of course, capitalism and communism. The former has grown into heavyweight intermediation over decades of wealth concentration and generational favouritism, which has morphed into powerful financial organisations which drive the whole system.

Half the population has negligible amounts of wealth, and disposable assets are effectively restricted to just the richest 30%. The situation will be even more acute post-pandemic than shown in this chart, which is not cumulative – the totals in each column are the total wealth in that decile.

Wealth inequality cannot only be seen across the breadth of the population but also by age cohorts, with generations born after 1970 having significantly lower levels of home ownership.

There is no doubt that capitalism and the market economy are at the heart of wealth creation, fostering enterprise and creativity and encouraging the best from people: and yet the rich get richer, the poor poorer and the average age of wealth increases: until something snaps and very large numbers of people with no hope say: “up with this we will not put”. Then the pendulum swings once more.

Democratic capitalism which is not anchored by measures to give genuine equality of opportunity, particularly for the young, is doomed to experience dramatic reverses and to impose a serious degree of unhappiness.

However, communism was designed for heavyweight intermediation in the first place, intended to be controlled by a ‘benevolent’ dictatorship which ensures that everyone is a vassal of the state, with little opportunity to be in control of their own destiny.

Excess intermediation, whether by the state or by financial institutions, has failed: the stark evidence of its failures stands out for all to see in the collapse of the Soviet Union, the 2008 financial crash and various violent revolutions over hundreds of years. Societies swing between the two systems like a pendulum, reacting against the excesses which reflect the shortcomings of their controlling powers.

The human condition is not one which should be ruled by others: disintermediation should be one of the yardsticks by which the effectiveness and fairness of economic systems are measured. Disintermediation requires that the impact on the individual is taken into account, and the need for people to take individual responsibility and control recognised.

A truly effective sense of ownership is built over time, and is best accompanied by a combination of learning and earning - in the widest sense. It is the contrast between ‘give a fish to feed for a week, or teach to fish to last a lifetime’. Micro-finance has shown our effective this can be, not only for the individual but also for their local community.

Contrast this with an inheritance passed down to fortunate descendants who have played no part in its construction, or to the winner of a lottery prize who may be delighted by their good fortune but has no idea how to handle it. Effective inter-generational rebalancing relies on inter-weaving both finance and life skills.

The gift of potential when human life begins makes no distinction for nature; in terms of socio-economic conditions, race, creed, nationality or other; yet, as Antoine de Saint Exupéry pointed out in the epilogue of his book ‘Wind, Sand and Stars’, it is often smothered by nurture: leading to a subservient underclass pushed about by the intermediation of others.

It’s for all these reasons that we are passionate for a more egalitarian form of capitalism.

True respect for others will enable every individual to have a stake in the society in which they live, and provides real opportunity for young people to achieve their potential. And respect for others is most effective when it is disintermediated.

This is not just a short-term endeavour: it’s calling for a permanent re-structuring which results in genuine ownership and responsibility. It’s inter-generational, and it means tackling both wealth polarisation and the huge shortfall in financial awareness.

At the heart of an egalitarian capitalist society must be these principles of free enterprise and individual liberty, as espoused by Thomas Jefferson 200 years ago.

Egalitarian capitalism is about people from all walks of life having the opportunity to experience a genuine sense of ownership and to feel in control of their own destiny.

It’s not about searching for short-term palliatives: it’s about looking for a permanent structural change which will fire up each new generation with the resources and life skills needed to achieve their own potential.

If we can introduce a reliable model in the United Kingdom, it should be exportable: we can literally change the world with this new approach to economics.

Egalitarian capitalism should enable people from all walks of life to make the journey from working for money towards the point where money works for them, so that we no longer see capital and labour as protagonists across society; but where both are available to all.

There are two strands to my approach: the first, for our current adult generations, and the second, for the young and generations to come.

For adults, it means a programme of determined capital participation. Some may claim that the term ‘egalitarian’ does not correspond with the basic tenets of capitalism: but that only serves to explain the problem with the traditional view of it. Margaret Thatcher may have tried to label it as ‘popular’ in the 1980s, but unless all can share in wealth creation it will always be seen as elitist.

Some of the key ingredients for this capital participation for all are:

- a new drive for personal share ownership, in order to re-connect people with business, including encouraging Covid-19 based increases in the savings ratio to move into equities, a substantial increase in voting, and fiscal encouragement for investment clubs, recognising their ability to build confidence in risk assessment and knowledge of investment – this to include new issue participation and a close look at the operation of pre-emption rights;

- re-balancing the scales between private equity and public markets, to include looking at the treatment of interest, stamp duty, the burden of regulation, and the bias towards business trade sales as opposed to retail flotations; and

- reviewing whether initiatives such as ‘shared ownership’ do in fact boost home ownership, particularly for young people, and the psychological interplay between personal debt and investment.

But all of these will only shift the dial slightly: it is the technological revolution which gives us a real opportunity to move swiftly into widespread capital participation, introducing a new programme for data storage and harvesting by tech giants to be recognised in share ownership for their customers.

The Digital Markets Unit within the Competition and Markets Authority is tasked, amongst other things, with investigating and reacting to the exploitation of data. Meanwhile in the US, Congress is clear that tech power has reached such levels to allow it to hoover up competition at will, and needs to be checked.

In Yanis Varoufakis’ book ‘Talking to My Daughter - a brief history of capitalism’, he addresses the economic impact of deep automation at every level of society, in a chapter entitled ‘Haunted Machines’. His concern about the comprehensive replacement of human labour with robotics is clear, but he also appreciates the dichotomy presented by the inevitable march of technological progress.

In Yanis Varoufakis’ book ‘Talking to My Daughter - a brief history of capitalism’, he addresses the economic impact of deep automation at every level of society, in a chapter entitled ‘Haunted Machines’. His concern about the comprehensive replacement of human labour with robotics is clear, but he also appreciates the dichotomy presented by the inevitable march of technological progress.

The tech giants’ concentration of wealth is staggering, and hardly a day passes without some report of the deployment of excessive wealth concentration in vanity projects such as space tourism. No wonder Varoufakis says: ‘Our creations - the machines installed in every factory, field, office and shop - have helped produce a great many products and have changed our lives utterly, but they have not eradicated poverty, hunger, inequality, chores or the anxiety about our future basic needs’.

So, there is also a fundamental economic instability in this process, because machines, unlike human labour, don’t spend money. Rather, they hoover up the money circulating in the economic system at large, and they deposit it at the disposal of their super-rich masters, instead of letting employees’ weekly expenditure fuel the income for others throughout society.

Some economists have tried to address this by proposing a ‘Universal Basic Income’, but this is surely looking for the lowest common denominator, or ‘levelling-down’: a route by which the vast majority of humanity will be left on subsistence terms while Bezos, Zuckerberg and Cook fill their palaces with gold and the sky with rockets and satellites.

A current Amazon advertisement says ‘At Amazon we don't just think big - we do big’. A couple of weeks ago when Jeff Bezos converted the revenues from millions of his customers into his single space trip on 20th July, we had a graphic example of the economic impact of monetary hoovering.

A current Amazon advertisement says ‘At Amazon we don't just think big - we do big’. A couple of weeks ago when Jeff Bezos converted the revenues from millions of his customers into his single space trip on 20th July, we had a graphic example of the economic impact of monetary hoovering.

The answer lies in democratising the equity ownership of the tech giants - and, because their masters will not enable this voluntarily, Governments need to set the criteria by which this is to be achieved. For, if the majority of humanity - who almost all use the services of big tech – were to see their working wages gradually being replaced by regular dividends from that equity ownership, we will achieve a society in which all can benefit from the massive boost in experiential wealth which automation is bringing about.

So, we should use big tech’s huge storage and harvesting of our personal data as the currency for distribution of their equity shares to their customers. We’re all aware that the tech giants sit on an immense store of data about us; GDPR has done almost nothing to rein in their intrusion into our personal lives.

And this will achieve two great benefits: firstly, that there will be democratic control over the way they behave (including that check on anti-trust behaviour) and secondly, that the flow of dividends will replace the huge quantity of lost money that their automation is gradually sucking out of circulation.

Of course, a permanent re-structuring to enable capital participation for all also means applying an inter-generational ratchet in order to ensure that each new generation is endowed with the opportunity to achieve their full potential. So, we’ll turn to that next.

In a society where, as David Willetts has explained in his book ‘the Pinch’, the vertical link between generations is so strained, inter-generational rebalancing is particularly relevant. For example, there are proportionately far more young people born into disadvantaged black and minority ethnic families than into those of wealthy white people. If no ratchet is applied to capitalism, their only economic hope for the future is through state intervention.

The denial of hope and opportunity to young people is most acute for black and minority ethnic people. The root cause of racial injustice is economic inequality: inter-generational rebalancing, provides the solution for resolving that inequality.

So, the way forward for inter-generational rebalancing is to combine starter capital accounts with incentivised learning: the latter, so that there is a strong sense of the young person having ‘earned’ the assets.

The vehicle for these starter capital accounts would be closely aligned with the Child Trust Fund. There are six million young people who have these individual accounts throughout the UK: in the context of egalitarian capitalism, they provide individual ownership for all.

The vehicle for these starter capital accounts would be closely aligned with the Child Trust Fund. There are six million young people who have these individual accounts throughout the UK: in the context of egalitarian capitalism, they provide individual ownership for all.

A Government endowment today using the Junior ISA account, would only apply to those young people whose families and background leave them without hope of meaningful family inheritance. The ‘catch up’ for those under 18 who do not currently have a Child Trust Fund would entail a one-off commitment of about £5 billion: but, in the steady state, just a quarter of current inheritance levies targeted at empowering these young people would enable accounts to be established with an initial £1,000, with £1,000 more to follow at age 7.

An incentivised learning programme would be introduced alongside this starter capital account, to offer the opportunity for these young people to ‘earn’ a further £3,000 each and, in so doing, prepare themselves to be ready for a fulfilling and economically rewarding adult career. Operated at national level and offered to young people most in need, it would reward those who make the effort to progress through a structured programme of building their life skills with small but meaningful tranches of capital to provide a resource base for starting adult life.

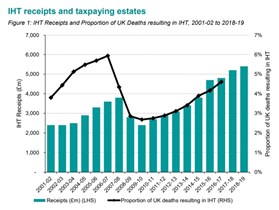

Now you may ask, how do we finance this permanent ratchet designed to empower disadvantaged young people? The answer is from the proceeds of Inheritance Tax.

Inheritance Tax is a levy on privately-owned capital which is placed into the Exchequer and then spent as current public expenditure. The process is therefore used to move private sector savings and investment - put aside for tomorrow - into the public sector running needs of the present.

Inheritance Tax is a levy on privately-owned capital which is placed into the Exchequer and then spent as current public expenditure. The process is therefore used to move private sector savings and investment - put aside for tomorrow - into the public sector running needs of the present.

HM Treasury's aversion to hypothecation is well known, and of course the proposed financing for inter-generational re-balancing could be drawn from the pool of current spending: but logic suggests that the proceeds of IHT levy, which is paid by less than 5% of estates (therefore by those in the wealthiest cohort) at rates set by the Government in power, should at least in some part be employed in financing inter-generational rebalancing.

Then there is the need for financial education.

The ‘T’ level Finance exams start this year, but subject choices in A-levels, essential for university and heavily influenced by university entrance guidelines, and in GCSEs, do not include financial awareness. As a result, financial education in schools is very patchy: surveys show that less than 25% of young people consider themselves properly prepared, and future teachers are emerging from universities and teacher training colleges not equipped to teach the next generation of young people in schools in financial education.

The ‘T’ level Finance exams start this year, but subject choices in A-levels, essential for university and heavily influenced by university entrance guidelines, and in GCSEs, do not include financial awareness. As a result, financial education in schools is very patchy: surveys show that less than 25% of young people consider themselves properly prepared, and future teachers are emerging from universities and teacher training colleges not equipped to teach the next generation of young people in schools in financial education.

We need a comprehensive and determined approach for improving financial capability:

- A mainstream ‘Financial Awareness’ GCSE, designed to test progress with financial education in schools;

- Guidelines for universities asking schools to bring forward qualifications in life skills and in particular financial capability, and for producing financially capable teachers;

- A new focus on primary financial education, which is when saver/spender attitudes start to develop;

- Proposals to encourage employers in both private and public sectors to provide more adult training in financial awareness. Such training for their staff should be made an allowable expense against gross income.

Plus, we need fresh ideas designed to reduce or cancel student debt, which hangs like a psychological albatross from the neck of university graduates, reducing their appetite for taking entrepreneurial risk or embarking on home ownership.

So, if we're going to change the world economic order over the next few years, it will require not just speaking at excellent gatherings like this but also some positive action.

Firstly, politicians and international states people will require real academic rigour behind the proposals. That's why I'm working with Cambridge University to introduce a four-year research fellowship under the acronym SHARE to build a convincing case. Please send me an email if you’re interested to hear more.

From a commercial point of view, I've tried to move the dial in the UK over the past thirty years with The Share Centre. Our whole focus has been on building personal share ownership, improving shareowner engagement, and helping people take control of their own investments - pursuing disintermediation. Again, please get in touch if you can help.

And, for inter-generational rebalancing, The Share Foundation is very active in empowering young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. We've pioneered incentivised learning and can show that it works, and we're now helping to make the Child Trust Fund a reality for those reaching 18 over the next few years, to prove how effective it is and to provide evidence for its re-introduction on a more progressive - and permanent - basis. If you’d like to help, please consider becoming a Child Trust Fund Ambassador.

In summary -

People don’t like the removal of their control over their own lives, whether as the result of the state or excess intermediation by financial institutions.

People don’t like living in a society where the rich get richer and the poor, poorer.

These are the two basic reasons why egalitarian capitalism matters.

Margaret Thatcher may have pushed for these concepts in the 1980s, but institutional intermediation, privilege and wealth polarisation remain with us today.

It is now forty years since Sir Keith Joseph spoke of breaking the ‘cycle of deprivation’.

A few years before that Martin Luther King said ‘The American dream reminds us that every person is heir to the legacy of worthiness’.

Yet little has happened.

Now is the time for change.

Gavin Oldham OBE