“To trust people is a luxury in which only the wealthy can indulge; the poor cannot afford it.”

E.M. Forster

As the Brexit tension rises each day it’s hard to avoid focusing on it. Some would say ‘that’s been the Government’s problem for the past two years’ and many in business and society just want to move on so that other pressing issues can be addressed.

So last week I particularly enjoyed the launch of St. Mary’s University’s new School of Business and Society. The main speaker was Andrew Bailey, Chief Executive of the FCA, with former Conservative Minister - now Professor - Mark Hoban and former Labour Minister - now Pro-Vice Chancellor of St. Mary’s - Ruth Kelly. Brexit hardly got a look-in.

Their key theme was trust, and restoring people’s confidence in business and finance will be a key objective for St. Mary's new School of Business and Society.

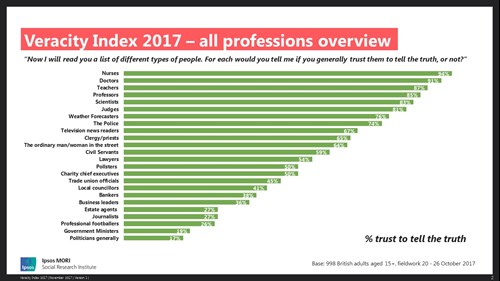

In October 2017 Ipsos MORI carried out the survey for their regular ‘Veracity Index’ series, which they have been running since 1983. The main question in the survey was: “Now I will read you a list of different types of people. For each, would you tell me if you generally trust them to tell the truth, or not?”

The bottom two professions are ‘Politicians generally’ and ‘Government Ministers’. ‘Business leaders’ were just six from the bottom out of 24, and ‘Bankers’ came in at seven from the bottom.

So what is it that causes failure of professional trust, and how can it be addressed? This was the challenge which Andrew Bailey addressed last Tuesday.

His analysis started with an article in 1970 by Milton Friedman, who argued that the notion of rational self-interest embraced the theory that ‘the social responsibility of business is to increase profits’. Andrew identified the mid-1980s as the point when all this started to go to senior people’s heads and lead to excess: particularly in their remuneration.

Having myself lived through the huge cultural change in finance in 1986 that was the ‘Big Bang’, it is clear that the cause for that excess, and for the destruction of trust in finance, was its ending of the separation of principal and agency roles. Everyone needs a clear motive for what they do: ‘acting as principal’ means you take the risk and the rewards of trading your own book, while ‘acting as agent’ means you always act on behalf of your customer, aiming to achieve the best for them.

Four years ago, Brian Winterflood and I discussed this on Share Radio with Simon Rose. Brian has always been a principal, the best-known market-maker in the City. Since the ‘Big Bang’, I have always been an agent: first in setting up Barclayshare, then The Share Centre: both on behalf of personal investors. But before ‘Big Bang’ I worked for nine years in a market-maker, Wedd, Durlacher, Mordaunt: so I understand that motivation too.

I believe the real cause of the 2008 financial crash and the collapse of people’s trust in finance was because people working in these industries, including those at a senior level, could not handle the conflict of interest which comes with acting as both principal and agent. Self-interest simply took over and, when endowed with the privilege of direct access to customers, it became rampant. The step change in banking culture was almost tangible.

It’s my view that those who lead and design regulation still don’t get this, even now. Furthermore, attempting to cope with polarised motivation seems to have fed its way into business and politics more generally, and I would suggest that that is why they are at the bottom of the Ipsos MORI table too.

Holding opposites in balance is very difficult by any measure. Perhaps that’s also why Theresa May is having such a struggle to find the answer for Brexit. Those on the EU side of the table are clear in their motivation: firstly, to keep the United Kingdom in and, failing that, to deter any other country from following. She, meanwhile, is trying to achieve that elusive balance between leaving and remaining - without much help from anyone. But at least she has integrity, unlike those responsible for the financial crash.

Andrew Bailey suggested that it was about standards, and St. Mary’s new School of Business and Society may help to re-establish a proper understanding of values.

At The Share Centre, there is a clear set of values to guide the business and, so far as humanly possible, they shape behaviour day by day. The value which most relates to trust is ‘long-term stability’, because people have to know that you are consistent and reliable in order to trust you. But there are two other values which are really important in underpinning that long-term stability: ‘respect for others’ and ‘empowerment’.

‘Respect for others’ means a genuine care for the interests of others: it means walking alongside people, not talking down to them, and understanding their journey whatever their circumstances. ‘Empowerment’ means sharing generously to help others to achieve their potential, more often than not by democratising expertise.

If we are to reverse the lowly position of politics, business and finance in the Ipsos MORI Veracity Index, these three values need to be fully embraced by all these professions. And I would add one more: ‘humility’. It may be a difficult one to include in a corporate set of values, but it might help reduce the arrogance that can accompany positions of power and influence.

In this respect, it may be helpful to end with a quote this week - from St Mark’s Gospel, Chapter 10: “You know that those who are regarded as rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and their high officials exercise authority over them. Not so with you. Instead, whoever wants to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wants to be first must be slave of all. For even the Son of Man did not come to be served, but to serve ..”.

Gavin Oldham

Share Radio