“Seas rise, crops wither, wars erupt. Humankind again seeks shelter in another place.”

National Geographic front cover, August 2019

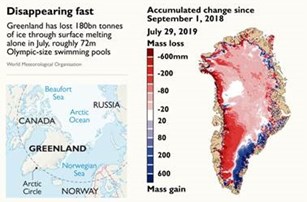

The most worrying statistic of the past week was not Mark Carney’s gloomy outlook for the UK economy, but the fact that the release of water from the Greenland ice sheet in the month of July alone will cause a 0.5 mm rise in the global sea levels (Times, 31 July: ‘Disaster looms as Greenland ice melts’).

The most worrying statistic of the past week was not Mark Carney’s gloomy outlook for the UK economy, but the fact that the release of water from the Greenland ice sheet in the month of July alone will cause a 0.5 mm rise in the global sea levels (Times, 31 July: ‘Disaster looms as Greenland ice melts’).

Migration is forced to take the strain when other human intervention fails. This may be as a result of:

- Economics, for example caused by imposition of fixed currencies, or by dysfunctional governments; or

- Conflict, as in Syria, Afghanistan or Myanmar; or

- Environmental damage caused by climate change

The first two drivers for forced migration have been with us for thousands of years: Jesus Christ started life as a refugee. We haven’t started to experience the third to any significant extent yet, but young people alive today will see its massive impact, yet to come.

When the whole of Greenland’s ice sheet is melted, global sea levels will have risen by five metres: so the fact that, in the last month alone, one basis point of that movement has already occurred should make us all sit up and take notice. The accelerating rate of glacial melt on Greenland is critically important for billions of people throughout the world, and we are reaching the point where mitigation in anticipation of sea level rise, where possible, is unavoidable.

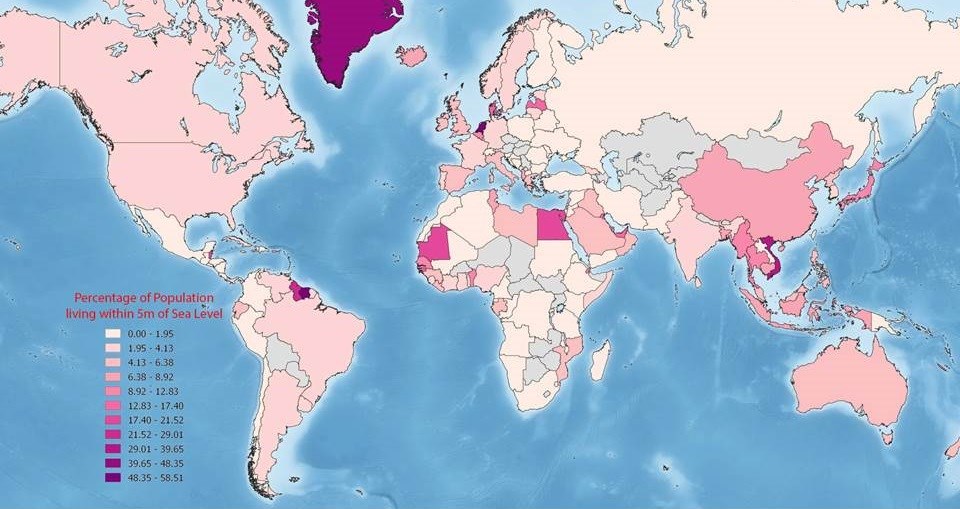

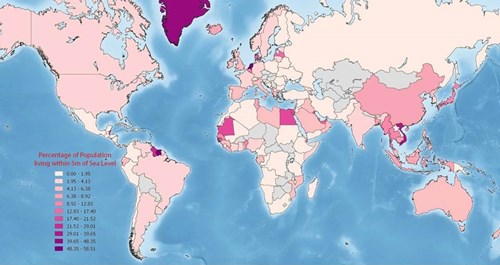

This image from Reddit gives an indication of the percentage of populations living within that five metre band above sea level around the world. A moment’s glance confirms that there is massive migration ahead, particularly in, for example, Egypt (population 98 million, c. 25%) and China (population 1.4 billion, c.10%) - but it affects all continents.

Speaking of mitigation, and given that the loss of the Greenland ice cap is now almost inevitable, the population density living within five metres of sea level around the Mediterranean makes a strong argument for a barrage to be built across the Straits of Gibraltar: this would protect thousands of centres of population, including around the Black Sea. The United Kingdom had the foresight to save London by building the Thames Barrier – similar foresight is now called for on behalf of the 21 countries bordering the Mediterranean.

Speaking of mitigation, and given that the loss of the Greenland ice cap is now almost inevitable, the population density living within five metres of sea level around the Mediterranean makes a strong argument for a barrage to be built across the Straits of Gibraltar: this would protect thousands of centres of population, including around the Black Sea. The United Kingdom had the foresight to save London by building the Thames Barrier – similar foresight is now called for on behalf of the 21 countries bordering the Mediterranean.

But the main purpose of this commentary is not solely to drive home an ecological point, although it does help us focus on yet another area where lack of human forward planning causes massive disruption in people’s lives.

I have been a subscriber to National Geographic for many years, and the current August edition focuses on migration under the title ‘World on the Move’. It’s a good issue because it presents not only the hard statistics but also the human reality of forced migration.

There’s also a chart setting out net national immigration and emigration as waves, over the past 50 years. For example, it shows the extent of immigration into the United States, possibly causing the populist reaction which brought Donald Trump to the presidency. The exodus from Syria stands out, but also the continuing outflow of people from India, China and Bangladesh.

In contrast, United Kingdom net inflow has been modest; and Spain is the only European country showing a recent outflow, although elsewhere in the article there’s a focus on migration from East Africa to Spain, mainly due to an agreement with Morocco to welcome agricultural workers.

Where time allows for assimilation to settle migrant communities, migration should be welcomed. It draws people together, and helps us to understand each other’s differences. But when events such as conflict, intense economic disadvantage and climate change force the pace, thereby requiring too much adjustment, too fast - within just one generation, for example - that’s when social stability is threatened and political reaction occurs.

Because large-scale, more frequent migration is inevitable due to climate change, we must learn to cope with it better: that’s why initiatives such as the recent book ‘Migrations – Open Hearts, Open Borders’ from ICPBS at the University of Worcester, will become increasingly important.

In some areas, such as economics, market forces can allow exchange rates to take the strain in adjusting imbalances: however, the more we try to fix currencies, the more we cause pressure to build up - so that migration becomes the only release valve available. That’s what premature imposition of the Eurozone has caused, for example. The consequences - albeit modest on a global scale - are not only unsettling all forced to migrate to find work but almost certainly became the key driver behind the Brexit decision in the UK’s 2016 referendum.

However, this will pale into insignificance when compared to the population movements which will be required by sea level rise: that’s why the Times article on 31st July is of such concern, and why we must get a grip on climate change to avoid it becoming even worse.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio