“I feel about airplanes the way I feel about diets. It seems to me that they are wonderful things for other people to go on.”

Jean Kerr

The news last week that Boeing fell to its first loss in 22 years brought the current crisis in commercial aviation into sharp focus. $19 billion has been earmarked to pay for the prolonged grounding of the 737 Max, including $8.3 billion for rapidly escalating airline compensation, $6.3 billion for additional production costs, and $4 billion for abnormal production costs. This does not include compensation for families of crash victims.

Commercial aviation is, however, challenged by more than Boeing’s ‘Deepwater Horizon’ moment (BP’s massive oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010). Airbus, the huge European aircraft manufacturer, is going to have to weave its way swiftly into the new UK–EU trade deal, notwithstanding last week's £3bn corruption penalty. And all the while climate change consciousness is rising, challenging both travellers and the travel industry to take responsibility for their carbon footprint.

So in this commentary we look at aviation at the crossroads: 70 years after the jet engine revolutionised air travel, is it time for the next great breakthrough - and what could that be?

My first job was as an unskilled fitter in British Aircraft Corporation’s Weybridge factory, working on the wings of the BAC–111 aircraft. The late 1960s were an exciting time in aviation: the Concorde prototype was also under construction in that same factory, and post-WW2 design and innovation was at its zenith.

Much has changed over the past 50 years, such that commercial aviation has turned into a commodity for mass travel. And with that change has entered a move away from the search for excellence, to the extent that employees working on Boeing’s 737 Max programme joked that the aircraft was “designed by clowns” who were “supervised by monkeys”.

As a result, Boeing has undergone a massive shock to its record for profitable and reliable delivery. Don’t worry, however, that the company itself might be in threat of bankruptcy: it not only has massive cash resources and re-financing options, but also Uncle Sam would quickly deliver a hugely over-priced military programme bailout if the company were to appear under threat.

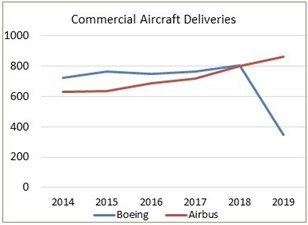

Boeing’s big international challenger is Airbus, which is now moving ahead in terms of aircraft deliveries (source: Forbes). But the UK’s departure from the European Union means that urgent action will have to be taken to ensure that there is no disruption to the multi-national construction programme, in which the UK plays a major part (for wings and engines in particular). Boris’s trade agreement team will be looking carefully into many sectors requiring special attention, such as cars, fishing and finance (see our new year commentary on retail investment), but Airbus demands special attention.

Boeing’s big international challenger is Airbus, which is now moving ahead in terms of aircraft deliveries (source: Forbes). But the UK’s departure from the European Union means that urgent action will have to be taken to ensure that there is no disruption to the multi-national construction programme, in which the UK plays a major part (for wings and engines in particular). Boris’s trade agreement team will be looking carefully into many sectors requiring special attention, such as cars, fishing and finance (see our new year commentary on retail investment), but Airbus demands special attention.

Additionally, Airbus has just had to accept record fines for corruption.

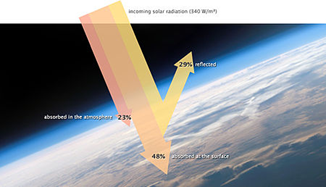

The challenges don’t end there, however. Aviation may only be responsible for 2% of human-induced carbon emissions (12% of all transport), but it favours a much smaller proportion of the world’s population in terms of lifestyle. Meanwhile the demand for holiday air travel is falling swiftly, as people are becoming more climate change conscious. In a few years’ time many other operators will follow Thomson Travel into the archives. It is simply not acceptable for dedicated air travellers to point their fingers at cows as much larger carbon emitters: it’s time for a change in attitudes among the business and international elite.

So, what might be the next steps for commercial aviation? While research is underway into electrically-powered aircraft, it is highly unlikely that this will provide for other than very short haul flights and general aviation requirements.

The obvious candidate as a fuel is hydrogen, which just produces water: so no carbon contribution to climate change, although cloud-seeding at 30,000 feet does result in a small warming influence (‘Radiative forcing’). On a visit to the Rolls-Royce stand at Farnborough Air Show 15–20 years ago, I asked what progress was being made with hydrogen. I was assured that research was underway - but it’s a long time coming. Fuel storage on board an aircraft is, of course, a major issue. In the past few weeks, we’ve heard much about progress with hydrogen powered cars - what about aircraft?

The obvious candidate as a fuel is hydrogen, which just produces water: so no carbon contribution to climate change, although cloud-seeding at 30,000 feet does result in a small warming influence (‘Radiative forcing’). On a visit to the Rolls-Royce stand at Farnborough Air Show 15–20 years ago, I asked what progress was being made with hydrogen. I was assured that research was underway - but it’s a long time coming. Fuel storage on board an aircraft is, of course, a major issue. In the past few weeks, we’ve heard much about progress with hydrogen powered cars - what about aircraft?

But the real ‘holy grail’ for aviation is understanding how to counteract gravity to provide vertical take-off and therefore how to abolish the need for air-driven lift, so that forward propulsion is the only call for fuel. Considerable progress was made during WW2 in this field: German research and innovation was well-charted in Nick Cook’s 2001 book, ‘The Hunt for Zero Point’. The United States swiftly absorbed that knowledge into its space and defence programs, and it is said that the Stealth bomber makes use of some of this technology. Paul LaViolette’s book ‘Secrets of Anti-Gravity Propulsion’ is also well worth a read.

The need for aviation will not go away, but modern-day researchers and scientists must look urgently for the next breakthrough. That is why aviation is at the crossroads today, just as trains were in the 1960s, when the age of steam drew to a close.

A final thought: most employers will be aware of the concentration of staff ‘days off sick’ following holidays involving air travel – indeed the circulation of germs in cabin air conditioning systems has been highlighted in the current spread of coronavirus. Is it not high time that all commercial aircraft are required by law to install sterilisation air filters in their air conditioning systems?

Gavin Oldham

Share Radio