“Let any one of you who is without sin be the first to throw a stone.”

Jesus Christ

I wonder if Mitch McConnell, when he cast his vote of ‘Not Guilty’ in the Senate trial of Donald Trump last Saturday afternoon, was thinking of this quote from the gospel of St. John. I doubt it: from his speech after the vote took place, it was clear that he was ‘dancing on a pin’ to find an explanation for the way he voted.

On Wednesday 17 February, the Christian season of Lent begins: traditionally a time when people are encouraged to examine their conscience. Former President Trump doesn’t appear to be doing much of it, but that’s par for the course for commercial property folk - witness the unwillingness of UK freehold developers of high-rise blocks of flats to step up to the plate, rather than pushing the costs of re-cladding onto their leaseholders.

So in this commentary we take a deep look at the mysterious, God-given human characteristic of conscience.

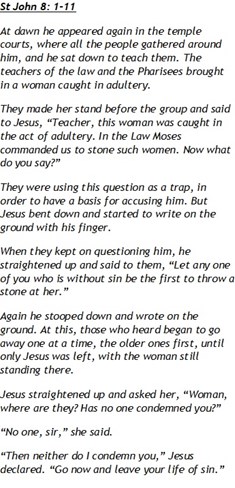

The most direct teaching about conscience in the New Testament is to be found in the eighth chapter of St. John’s gospel. This story, when Jesus was challenged with the case of a woman caught in adultery, carries several meanings within it. Firstly, in its concluding sentence it acknowledges the existence of wrong-doing. Secondly, it demonstrates the action of love to bring about reconciliation. Finally, it starts to teach us how to understand the role of conscience in that reconciliation.

The most direct teaching about conscience in the New Testament is to be found in the eighth chapter of St. John’s gospel. This story, when Jesus was challenged with the case of a woman caught in adultery, carries several meanings within it. Firstly, in its concluding sentence it acknowledges the existence of wrong-doing. Secondly, it demonstrates the action of love to bring about reconciliation. Finally, it starts to teach us how to understand the role of conscience in that reconciliation.

It’s particularly helpful to imagine what might have been passing through the mind of Jesus as he bent down and wrote on the ground - which must have been for several minutes, allowing for the crowd to disperse. I sense that he felt a deep sense of frustration at people’s unwillingness to embrace his message of love, to love their neighbour as themselves.

The closest human parallel with άγάπε, the selfless love which is God, is seen in the mother-child relationship. Of course, it’s not always perfect, but resort to harsh judgement is rare, as a mother’s whole concern is to build up, not destroy. It’s this recovery which Jesus was seeking in his response to the woman in the story.

There are other minds to consider here, however: the minds of those who accused the woman, as each turned away. They had been invited to look deeply inside themselves, and to examine their conscience, and it’s interesting to read that the older – and wiser? – recognized that challenge first.

Conscience is a difficult thing for religious folk - it simply does not conform to those rules and regulations which so many like to follow. For centuries, the Church has fought shy of its challenge, and it is difficult even today to find serious theological analysis on the subject.

In his ‘very short introduction to Conscience’, Paul Strohm recounts that Cardinal Ratzinger, who became Pope Benedict XVI, argued that a purely subjective conscience can err. He stated that a conscience-based sense of guilt is a specious and unnecessary form of consciousness, that needs to be addressed outside the arena of personal ethical choice.

All people, in Ratzinger’s view, possess a previously implanted love of truth and ‘the good’, but this faculty is at times forgotten - and humankind cannot be expected to recover it unaided. The role of Catholic authority, he says, is therefore to assist errant and forgetful people in the discovery of this hidden capacity.

He claims that conscience needs authority in order to hear itself or to discern its right objects.

For those who feel in need of such guidance, the Bible provides a wealth of reference, together with much of the debate on how to apply it. The Old Testament texts were available in the days of those teachers of the law and pharisees who accused the woman in the story, but it was the simple challenge of Jesus that sufficed to waken their conscience.

As Paul Strohm writes, ‘Conscience is like an independent judiciary; we can never be certain of its verdict, but it represents our best hope for a fair hearing and acquittal in the end’.

Particular challenges arise when religious and secular authority challenge each other, and conscience comes into its own to help resolve the dilemma, notwithstanding that uncertainty. For example, ‘Living in Love and Faith’ is a book produced by the Church of England containing Christian teaching and learning about identity, sexuality, relationships and marriage, and it contains this paragraph on conscience:

‘Conscience is not infallible. We can feel guilty when we do not need to. We can feel confidently innocent when we really should not. We can be driven by an anxiety about salving our own consciences when we should be willing frankly to admit our failings and trust in God’s mercy. Our consciences are shaped by all kinds of factors, and we can work together to form them well - by reading the Bible, listening to and learning from the Church’s teaching and from one another, and learning to trust in God’s mercy in Christ.’

This open conversation with ourselves and with others is the complete opposite of hypocritical judgement. It points directly towards reconciliation: it is about bridge building, and the greatest demonstration of that was to span the gulf between the perfect goodness of God and the human experience of living so close to chaos and darkness. That initiative, which lies right at the heart of the Christian faith, was Jesus’s redemption on the cross, breaking the veil between us and God: the perfect reconciliation.

It’s interesting to surmise how these issues may be playing out in the minds of American law-makers.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio