“The two lakes between Israel and Jordan have a principal feature in common and a basic difference. Both receive the waters of the River Jordan. The first, the Sea of Galilee, receives the water and shares it to fertilise the southern regions. The second, the Dead Sea, receives the water but keeps it for itself. In the first, there is plenty of life within its waters and around them. In the second, there is no sign of life.

“The two lakes between Israel and Jordan have a principal feature in common and a basic difference. Both receive the waters of the River Jordan. The first, the Sea of Galilee, receives the water and shares it to fertilise the southern regions. The second, the Dead Sea, receives the water but keeps it for itself. In the first, there is plenty of life within its waters and around them. In the second, there is no sign of life.

We have the privilege of receiving continuously the living water of the spiritual Jordan: that is, the unconditional love which is God. We receive continuously a great many gifts – spiritual and material. If we keep them only for ourselves, we shall lose them. The Dead Sea remains the symbol of what it means merely to receive and keep for oneself. If we share, we shall be like the Sea of Galilee, full of life.

Receiving and sharing is the secret for having life.”

Archbishop Anastasi of Tirana, Durres and All Albania

There is a common assumption that if your aim is to care and show respect for others then it is best done by intermediation, not as an individual. Even the Archbishop of Canterbury gave up on individuality at the General Synod last week, with his claim that individualism was both illusory and a fantasy. And yet, Jesus Christ's instruction to ‘love your neighbour as yourself’ was not an invitation for intermediation – rather, he sought to teach individuals how to respect and care for others, as Archbishop Justin himself acknowledges: ‘The challenges of our time go to the heart of understanding what it means to love our neighbour’.

Margaret Thatcher's quote that ‘there is no such thing as society’ was widely interpreted as a creed for self-interest: each for themselves, and the devil take the hindmost. The Archbishop repeated this denial of the possibility of individual generosity, stating ‘those who have, gain more, and those who have not, bear the consequences. The strong do what they will, and the weak suffer what they must’.

It ranks almost as a Little Red Book quotation seeking to justify intermediation across the world. Of course it's not difficult to find selfish and self-centred rich and powerful people: it was, after all, Jesus who said that it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of God. But his retort was not to dictate herd behaviour, but to encourage us to embrace the parable of the Good Samaritan.

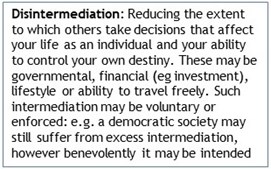

It’s reasonable to ask the question ‘why is it so difficult to identify a political movement founded on individual generosity?’ Why is the middle ground full of people who insist on intermediation to get their way? These are big questions for those of us who believe in egalitarian capitalism, where the yardstick by which it should be measured is the degree to which it encourages disintermediation.

It’s reasonable to ask the question ‘why is it so difficult to identify a political movement founded on individual generosity?’ Why is the middle ground full of people who insist on intermediation to get their way? These are big questions for those of us who believe in egalitarian capitalism, where the yardstick by which it should be measured is the degree to which it encourages disintermediation.

But as soon as a long-term perspective is taken and the opportunity to introduce inter-generational rebalancing with a new strategy for inheritance is taken into account, we can see that a surrender to intermediation is not the only answer, and that individuals from all backgrounds can have the opportunity to achieve their potential in life.

The point Margaret Thatcher was trying to make is that it is for each individual to find this balance between their own self-interest and their care for others. It is a process of individual learning and self-discipline: Government may be part of the catalyst for change, but humans are not herd animals.

Archbishop Justin went on to cite the tension between individualism and community as being interrelated with global inter-generational equity, technology, climate change and vaccine nationalism. He could have re-interpreted that second great commandment for our current era as including future generations as our neighbours since, unlike two thousand years ago, our actions today impact heavily on those generations to come: I spoke about this in a Radio 4 ‘Thought for the Day’ delivered on 2 March 2004.

But it doesn't change the fact that he, and other Christian leaders, should be teaching individuals about understanding their relationship with the divine, not seeking to endorse community intermediation like Archbishop Temple with the welfare state after WWII.

Intermediation easily turns into a denial of individual responsibility, as if it can be contracted out to those who pull the levers of power, thereby relieving the conscience. Archbishop Justin acknowledges the challenge facing societies which lose their moral compass: ‘A society that forgets about God, that loses the sense that it needs God, that no longer desires God, such a society loses the profound call to see the wholeness of the individual human person and the call to love, by that person being set free in relationship with others’.

Communism shows that in graphic detail.

Whether in the field of climate change, empowering the disadvantaged, interacting with technology, or keeping others say from viral infections, important decisions must be made at the individual level. The conscience should help to school our thinking as to whether we are individually putting too much carbon in the atmosphere, individually allowing our children to become addicted to online gaming, individually helping to feed the hungry or individually taking a responsible attitude to Covid-19.

Unfortunately, the Church, whose responsibility it is to carry the Christian faith forward from generation to generation, doesn't have much to say about conscience. One of the best examples of Christian teaching on conscience is the gospel story of how Jesus was confronted with a woman caught in the act of adultery. His reaction was not to challenge her conscience but those of her accusers: and they all went away silently, starting with the oldest.

At a meeting shortly before Christmas, I asked the Bishop of Oxford how best we can learn to understand what our conscience is saying to us. His answer was a single word: prayer.

And that speaks strongly of our need to find individual generosity through a personal individual relationship with our maker. It is not an invitation to hand over that responsibility to ‘the community’.

So perhaps those who advocate delegation of people’s need for a moral compass to ‘the community’ or ‘society’ should look closer within themselves, and ask whether that is actually a denial of the need to awaken the second great commandment within ourselves - a feature of humanity which I believe is hard-wired into our DNA, whether or not we believe in a conscious creator.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio