“The art of taxation consists in plucking the goose to obtain the largest amount of feathers with the least amount of hissing.”

Jean-Baptiste Colbert, finance minister to Louis XIV

The Chancellor sets out his Budget plans on Wednesday, and hopefully this will reflect a rather better record of receipts, and forecasts for the future, than when he last addressed the country’s finances in his Autumn Statement. The public sector is a hungry beast, and sometimes tax rates appear to reflect the art of the possible rather than any underlying principles.

It's nearly 250 years since Adam Smith formulated a set of principles for good taxation — these were fairness, certainty, convenience and efficiency. In 2011, the House of Commons Treasury Select Committee published its ‘Principles of Tax Policy’.

However, although there are references in the latter to international competitiveness, the principles are essentially domestic in character. It's also difficult to find any reference to inter-generational fairness — Adam Smith’s first principle is always referred to in the present, and long-term structural changes are generally absent from all such documents.

I recall some years ago attending a meeting in Cambridge with a gathering of Treasury experts when the issue of property taxation was discussed. The point made was that, whereas businesses and people can move to other countries if they feel overtaxed, property is locked to the ground and therefore a good target for dependable revenues.

In their view the principle of certainty referred to their being confident in the receipt of tax revenues, not in providing an accurate set of taxation rates on which everyone could rely — which is what Adam Smith had in mind.

Over recent years we've seen this ‘principle’ applied extensively in property taxation, with stamp duty now applying a maximum rate of 12% for the portion over £1.5 million — thereby causing considerable distortion and some illiquidity at the top end of the housing market.

Another area in which international mobility and competitiveness applies is that of corporation tax. Ireland would appear to have got the message here, with its 15% tax rate on corporate profits. Liz Truss made a brave, although foolhardy, attempt to bring down the UK rate, but this was swiftly reversed by Jeremy Hunt.

The logic for keeping corporation tax rates low is strong from a number of perspectives. Firstly, it attracts international businesses to your country, as Ireland has shown so impressively in its welcome for the tech giant headquarters. Secondly, as employment builds in those businesses, governments have plenty of opportunity to apply income tax and a whole raft of other personal taxation, including VAT on those employees’ expenditure.

So, what at first look appears simply a tax on an entity which has no electoral mandate is in fact ‘cutting off one’s nose to spite one’s face’ to deter businesses.

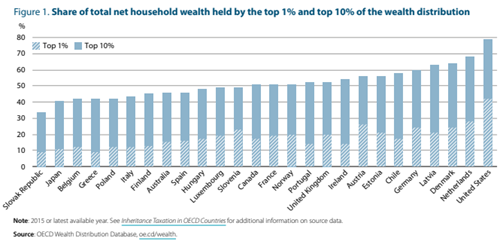

But the area where tax logic is most deficient is that of inter-generational fairness. It's hard to find any guiding principles for long-term structural change to help us address the chronic state of wealth polarisation, illustrated in the chart below, which is from the 2021 OECD report on inheritance taxation in member countries:

The report makes a good case for applying more consistency and logic to inheritance taxation but, apart from these references to the need to address wealth polarisation generally, it wholly misses the opportunity to link these receipts in order to empower young people from disadvantaged backgrounds with resources and life skills.

The long-term structural adjustment required for inter-generational rebalancing needs a constitutional presumption in favour of hypothecation. Inheritance levies, applied to long-term privately-held savings and investment, should not be swallowed up by the current spending requirements of governments whose primary interest is the short-term one of winning the next election. Rather, they should be earmarked specifically for provision of starter capital accounts and life skills for young people whose family/other backgrounds give them no hope of traditional inheritance.

The long-term structural adjustment required for inter-generational rebalancing needs a constitutional presumption in favour of hypothecation. Inheritance levies, applied to long-term privately-held savings and investment, should not be swallowed up by the current spending requirements of governments whose primary interest is the short-term one of winning the next election. Rather, they should be earmarked specifically for provision of starter capital accounts and life skills for young people whose family/other backgrounds give them no hope of traditional inheritance.

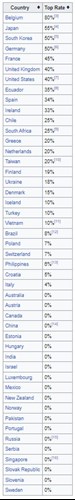

The UK Government collects £6 billion Inheritance Tax, with a top tax rate of 40% levied on estates. Inheritance taxes vary widely, as shown in the table alongside: it's interesting to note that China and Russia are among those with a 0% inheritance tax rate: clearly Marx didn't think in the long-term either. But there is no evidence of hypothecation, which would ensure that these levies are linked directly to young people from disadvantaged backgrounds: for example, Belgium, with the highest rate of inheritance tax still has 40% of household wealth owned by the top 10%, and the United States, with the same 40% Inheritance Tax rate as in the UK, has the most wealth-polarised society in the OECD: nearly 80% of wealth is owned by the top 10%.

If the Treasury Select Committee revisits its ‘principles of tax policy’, I would hope that long-term inter-generational rebalancing via hypothecation of inheritance levies is included in their recommendations, and that these will be made not only to HM Treasury but also to international bodies such as the OECD, G7 and G20, in order to provide individual opportunity for those with their adult lives ahead of them and who need it most.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio