“We are more fascinated today by statistical predictions of what the country will be thinking in a few weeks’ time than by visionary predictions of what the country will look like in 10 or 20 years from now.”

Peter Thiel, Author

One of the most significant comments during this Coronation period was The Princess Royal's reference to the significance of long-term governance, in her interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. The monarchy may appear anachronistic and symbolic, but Princess Anne is right to draw attention to the need for long-term governance: and at present it is not supplied by democracy.

There is an accelerating array of issues requiring the stability which a long-term focus should provide: for example, the environment, enabling all people to have an acceptable quality of life and standard of living, and ensuring that young people from disadvantaged backgrounds are not denied the opportunity to achieve their potential in adult life.

It’s also not only important to have a part of government which can itself plan for the long-term, but for government to contain the capacity to assess the merits of long-term proposals put forward by others. It’s difficult for ministers to lay claim to that competence when all the attention is focused on the next General Election. The democratic life cycle is short and, as demonstrated in current UK politics, made even shorter as the cadre of ministers with executive responsibility changes whenever when prime ministers are switched by Party sentiment.

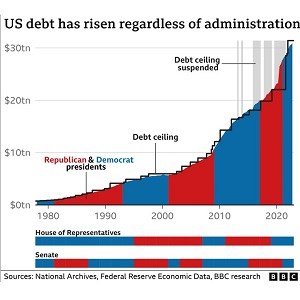

However, it’s not just here in the United Kingdom — across the world, from the United States to India, democracies really struggle with delivering long-term benefits and necessities to their electorates. Indeed, the U.S. has now built up its national debt to $31 trillion for future generations to service (Image source: BBC Research, based on National Archives and Federal Reserve Economic Data).

However, it’s not just here in the United Kingdom — across the world, from the United States to India, democracies really struggle with delivering long-term benefits and necessities to their electorates. Indeed, the U.S. has now built up its national debt to $31 trillion for future generations to service (Image source: BBC Research, based on National Archives and Federal Reserve Economic Data).

It's tempting to stay with the United Kingdom and the United States with this critique of democracy, but the contrast between India and China illustrates the issue in even more stark terms.

India is the world's largest democracy: indeed its population has now reached that of China, a total of over 1.4 billion people. China's population growth has, of course, been stunted by their ‘one child’ policy: this was introduced in 1980 and ended in 2016, having resulted in serious gender imbalance and a challenging demographic profile. However in terms of population density, China, with 397 people per sq. mile, is much less challenged than India with its 1,202 people per sq. mile (both, of course, significantly higher than Russia’s 23 people per sq. mile).

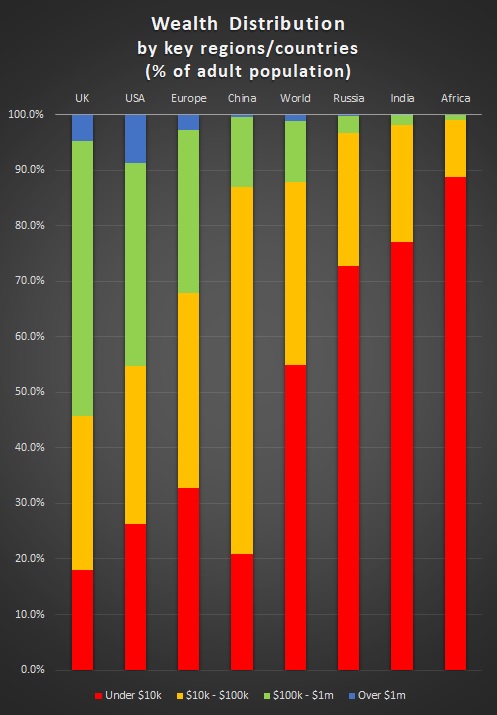

But it's their contrast in wealth profile which is most striking. A glance at the Credit Suisse Global Wealth database chart displays clearly how China has achieved at least a basic level of wealth ($10k - $100k per adult) for 80% of their population, whereas India has nearly 80% of its population in real poverty (less than $10k per adult).

But it's their contrast in wealth profile which is most striking. A glance at the Credit Suisse Global Wealth database chart displays clearly how China has achieved at least a basic level of wealth ($10k - $100k per adult) for 80% of their population, whereas India has nearly 80% of its population in real poverty (less than $10k per adult).

Western governments and media may rile against the autocratic and often harsh style of China's one-party government, but it has provided a long-term perspective which is almost completely absent in the West. We need to learn how to build that stability of long-term focus within a democratic context, and Princess Anne has correctly raised this requirement — although it’s fair to say that the British monarchy can do little more than draw attention to the need for its priority.

The first step would be to draw a clear demarcation line between long-term and short-term representative structures. The former must address matters of constitutional importance, particularly insofar as they impact future generations. The question, ‘How should the world look in 50 years’ time?’ would be appropriate for those electing these long-term representatives. The long-term assembly should retain a review role over short-term legislation to ensure that it is not out of step with long-term priorities, but day-to-day executive government would continue to be handled as at present.

What this calls for in the United Kingdom is a wholly-elected second chamber. During the first decade of this millennium a strong attempt was made to reform the House of Lords, but this dissolved in the face of pressure from vested interests. The current ever-growing membership, largely as a result of significant numbers of party appointees, does little to reflect electors’ concern for long-term issues.

As an interim measure, a Select Committee should be formed with a specific remit to consider long-term issues, to review proposed legislation in that context, and to invite fresh ideas for the well-being of future generations.

Meanwhile, as we proposed on 14 November 2022, our representatives at the United Nations should also be elected by the people, not appointed by government.

A thorough overhaul of our senior oversight structure in government should be undertaken to provide the necessary emphasis on long-term stability. The logical way forward would be to ask the King to chair this process, due to that long-term royal perspective to which Princess Anne referred.

If we can make the change here in the United Kingdom, other democratic nations should follow suit: also, taking a similar opportunity to elect their UN representatives. Over time we will build a new consensus for long-term democratic responsibility for to mirror that which the Chinese Communist Party has introduced through its autocracy.

There may, of course, be people in power who claim that the electorate would find it impossible to differentiate between the short- and long- term: I disagree. Family experience introduces almost everyone to the importance of leaving a world for our children and grandchildren which is both habitable and hopefully more peaceful and equitable than the one we are living in today.

At several times in the past, we have acknowledged the natural human tendency to discount the future, as explained by Nicholas Stern in 2006 in relation to climate change. If we can tackle democracy's struggle with the long-term, perhaps that discount rate can start reducing in order to give everyone a chance to look forward with hope.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio