‘Not everything that can be done, should be done.’

Rt. Revd. Peter Selby, former Bishop of Worcester

I recall this quote being made by Bishop Peter about twenty years ago, when I was a member of the Church of England's Ethical Investment Advisory Group. This committee helps the Church’s investment bodies by setting appropriate ESG criteria, and the context for this statement was the extent to which genetic modification of crops should be accepted.

This remains a big issue today: the United States has always allowed a high degree of genetic modification in its farming, which is why many countries — including The United Kingdom — placed restrictions on food imports from America. However, Trump's tariffing tactics have forced the loosening of these restrictions, and we must just hope that there will not be unwelcome consequences for people's health as a result.

Genetic modification has also been high up in the media over the past fortnight, following the news that embryonic human cells have been changed by replacing some with cells from a second woman. This has enabled the removal of a genetically-inherited condition called ‘mitochondrial disease’, and it may extend to other inherited conditions in due course.

Bishop Peter's quote is closely mirrored by the following two verses from St. Paul's first letter to the Corinthians, where he wrote:

‘“I have the right to do anything,” you say — but not everything is beneficial.

“I have the right to do anything” — but not everything is constructive.

No one should seek their own good, but the good of others.’

As with so many scientific innovations, genetic modification can be a blessing — but it can also be a curse. All such breakthroughs must be examined carefully in order to ascertain into which category they fall, and limits must be set accordingly.

This also applies to the rapid expansion of Artificial Intelligence into so much of our lives, and the analysis which is undertaken to assess its benefit — or otherwise — must take into account both short- and long-term considerations. These include the significant reduction in employment opportunities for young people and the challenge to creative copyright, with no corresponding participation in wealth creation.

Energy generation is another area which requires close examination and limits need to be set accordingly, and the impact of nuclear development must bear in mind its long-term challenges and risks.

This is not to say that people should revert to a neo-Luddite mindset of treating all things new with suspicion — or indeed with outright opposition — but care must be taken to ensure that the commercial drive for short-term progress, regardless of the wider cost, is not granted ‘carte blanche’. The current U.S. political environment is not only based on such short-term thinking but also on dominance in driving international agreements, and that's a combination of which we should be wary.

Setting limits to bring global warming under control is particularly challenging at present, and Trump's denial of fossil fuel impact is reversing much of the progress which has been made over recent years. The ‘1.5% over pre-industrial levels’ limit set as an acceptable maximum is clearly under threat, but the series of heatwaves, forest fires and catastrophic flooding seems to make no difference to U.S. presidential policy.

Trump continues to call for ‘Drill baby, drill’, and has even criticised the UK’s ‘unsightly windmills’ in his recent visit to Scotland.

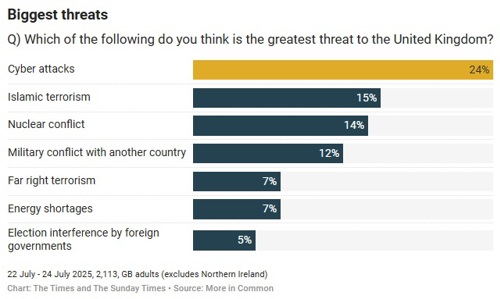

Environmental degradation did not even feature in The Sunday Times survey of biggest threats; this illustrates how long-term endemic changes can slip so easily out of the public eye:

Those with a long-term interest in global wellbeing must therefore be prepared to defend these limits even when they disappear from the politically-charged hot list.

This will remain a challenge in the UK while Nigel Farage’s Reform party stays in the ascendancy, although the planned reduction in minimum voting age to 16 should, in theory, encourage a longer-term perspective. In the meantime, it would help if the Government could show a bit more joined-up thinking, for example in its encouragement to make more use of electric vehicles.

Maintaining the veracity of limits is a major task which western democracies struggle with, particularly due to their short-term bias. As in the financial world, we need strong regulation to ensure that they are not overlooked.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio