‘Anyone who believes in indefinite growth on a physically finite planet, is either mad or an economist’

Sir David Attenborough

Autumn always starts with a burst of activity after the summer holiday months, but this year has been more active than most. Donald Trump has been primarily responsible, notably with his determined push for peace in the Middle East: as usual, it's been thoroughly unconventional, but it has worked.

Meanwhile, his tariffs have started exerting major influence on world trade and economic prospects: the impact on markets may be obscured by AI euphemism. However, warnings abound about the risk of a repeat of the dotcom setback 25 years ago, including in this week’s episode of This is Money, and in the statement from Jamie Dimon, Chief Executive of JP Morgan Chase, who warned last week of a potential market setback.

The Nobel Peace Prize Committee has, meanwhile, trod a very measured and diplomatic course in denying Donald Trump the ultimate accolade, although it may be hard not to award it to him in a year’s time if peace is maintained in the Middle East. The Nobel Committee’s emphasis on democracy as the basis for peace was striking, and there's no doubt that Maria Corina Machado deserves the award for her courage.

However, as we wrote on 16th December last year, democracy’s short-termism is also causing real problems for western economies. This year’s party conference season was full of calls for cutting migration and stimulating more economic growth — but are these two aims compatible? As statistics show, migration is almost entirely responsible for population growth in the United Kingdom. All political parties, however, seem to think that they can generate economic growth from a magic money tree while the size of our economically-active population falls.

They are surely living in cloud-cuckoo land in not recognising that you can’t have GDP growth without more young people.

Although world population growth has now reduced to 0.87% (or an additional 70 million people per annum), over the past 75 years it has quadrupled from 2 billion to 8.2 billion— enabling seven decades of unparalleled economic growth fuelled by all this new humanity. The United Kingdom, whose population has also risen but from 50 million to 69 million over the same period, has last year seen a 0.6% increase in overall population. But 94.4% of this growth is coming from immigration: so, without migration, the growth would fall to just 0.036%: that is just 23,000 per annum. Meanwhile, our birth rate has fallen to just 1.54 births per woman, well below the 2.1 required for a stable population.

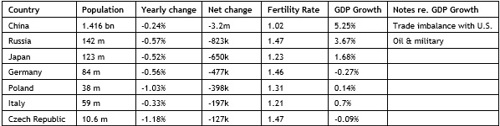

Significant reductions in population are now taking place across the world, with the largest falls being in:

It is a fact that, unless there are exceptional reasons otherwise, the primary drive for GDP (Gross Domestic Product) is population change; but politicians don't seem to be able to connect the two in their minds. Of course, there are exceptions to this: for example, China has taken huge advantage of their massive trade imbalance with the United States over the past two decades, but this is now coming to a shuddering halt as a result of Trump's tariffs. The average GDP growth for Japan, Germany, Poland, Italy and the Czech Republic is just 0.432% per annum.

In contrast, wealth creation is rarely dependent on population: the Middle East has shown this with fossil fuel extraction over the past 75 years, and the tech giants are now following their example — that is, unless significant steps can be taken towards the issue of widespread equity stock participation in return for people’s data and creativity.

This is why, if your working population is falling, you can't look to suppress migration while at the same time pushing for raw GDP growth. And it’s why most countries, including the United Kingdom, must therefore start focusing on GDP per capita as opposed to outright GDP as their key metric, and more use must be made of analysing standard of living and the quality of life.

This is why, if your working population is falling, you can't look to suppress migration while at the same time pushing for raw GDP growth. And it’s why most countries, including the United Kingdom, must therefore start focusing on GDP per capita as opposed to outright GDP as their key metric, and more use must be made of analysing standard of living and the quality of life.

There are two major concerns over current UK economic policy

The first is to stop pretending that Government can just spend its way into publicly-funded economic growth: it just doesn't work. Government is not like business when it comes to investment: it doesn’t evaluate investment returns properly, but instead chooses to spend regardless in order to stimulate an artificial sense of growth. There's no bigger example of this at present than the HS2 railway project. However, Rachel Reeves continued to lay out ambitious plans in her June announcement. Debt and taxes are already far too high with tax thresholds frozen for far too long, thereby making everyone feel hard done by.

The only way to get excessive public spending under control is to call a halt to universal welfare, as we proposed in our open address to Sir Keir Starmer before last year's election.

The Conservative Party also needs to accept this, and they should stop imagining that holding on to universal welfare is a necessary bribe to retain old people's votes, as if that's the only segment of the population that matters. As William Hague wrote in The Times on Tuesday 7th October, ‘Without young voters, the Tories are sunk’; it will take a lot more than stamp duty concessions to recover their appeal for the young.

This brings us to the second great inconsistency shared by political parties intent on achieving economic growth while cutting current immigration: the median age of the UK population is rising swiftly. In 1975, it was just 33 years of age: it's now over 40. If we don't prioritise our home-grown young people, they will leave for greener pastures overseas; and if we cut off migrants as well, our other main source of young people will be lost.

This is why we need a broad political acceptance of inter-generational rebalancing to be embedded into the constitution: not simply resorting to euphemisms about reducing child poverty. With so many children now born into unstable family circumstances, we must ensure that there is a reliable process of getting them the resources and life skills they need in order to achieve their potential in adult life.

The Share Foundation is totally committed to this pursuit, and looks to build on schemes such as the Child Trust Fund (where it has already linked £237 million of unclaimed accounts) and starter capital accounts and financial awareness training for young people in care in order to make this happen. But these Government policies should not be switched on and off at the whim of Treasury ministers: they require proper recognition of the opportunities provided by the human life cycle, including the £8.5 billion raised annually in inheritance levies in order to make them happen.

Let's hope some of this is recognised in the forthcoming November Budget.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio