“No-one has ever become poor by giving.”

Anne Frank

Rishi Sunak’s Financial Statement last Wednesday showed clearly his strategy for getting people into work. Almost all the concessions he made were focused on low earners: the substantial threshold increase for National Insurance, the advance notification of the first reduction in the basic rate of tax for many years. There was very little in comparison to support those on welfare benefits.

The UK Chancellor has done well to fire up the economy post pandemic by providing the furlough scheme, and his strategy to get Britain working again makes sense. However, as a nation we need to complement this with a strategy for sharing — particularly bearing in mind the huge escalation of energy prices. If HM Treasury is not willing to allow this to share the limelight alongside their work-based initiatives, there needs to be a plan established to encourage those who are prepared to improve the safety net for people on the breadline, and to improve the prospects for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

So in this commentary we look at how monetary, fiscal and capital dynamics could help ensure that the standard of living and future prospects for those living on subsistence is not impacted as heavily as indicated in current media predictions.

The war in Ukraine has filled this commentary for the past four weeks, but at last we are beginning to see a glimmer of hope. The cost in human lives and destruction has been horrendous, but it is also primarily responsible for the inflation rush which is impoverishing people on the breadline - and boosting tax income for the Government.

However Rishi Sunak is wise to be cautious about the extra income he is getting in: inflation has not yet had time to work its way into wages and, if a ceasefire were to be agreed in Ukraine, energy markets could soon adjust back down to more conventional levels. Of course, any such ceasefire would be tenuous - it will take years to rebuild trust between Ukraine and Russia, and only regime change in Moscow could speed up that process: but that's not inconceivable.

So in terms of monetary policy, the Bank of England is right to take its ‘one step at a time’ approach to raising interest rates: and, although the cost of servicing inflation-linked bonds is one of the main contributors to the £83 billion pencilled in for servicing public debt next year, that could adjust back down again quite swiftly.

It remains our view that technology and more flexible working arrangements are making permanent significant increases in inflation unlikely: once the current shocks are behind us, and bearing in mind that there will need to be a Marshall-type plan for rebuilding and revitalising Ukraine after the war, we will see low rates of inflation - and interest - again.

In fiscal terms, Sunak is understandably using the current situation to re-establish strong public finances post the pandemic, and to prepare for releasing more brakes before the next UK General Election: now probably just two years away.

But more has to be done to put in place a strategy for sharing; and that must look at both capital and welfare, including inter-generational rebalancing.

Let's look at capital first.

At present, there is very little recognition of the contribution that capital can make for those considering philanthropic endowments: shares have to be given ‘in specie’ to enable them to avoid Capital Gains Tax. There is no provision for charitable donations to be offset against tax due in the same way as there is for income.

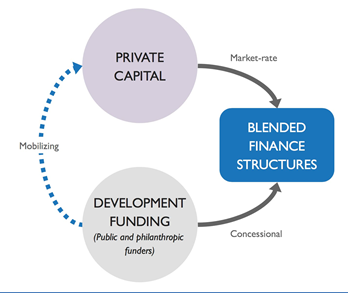

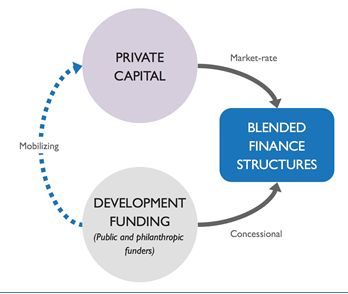

Meanwhile, last Tuesday I attended a webinar on blended finance — a technique for using philanthropic capital to reduce the risk levels for conventional impact investment: a rather complex process set out by the Canadian company ‘Convergence’, but at least an initiative which provides a set of private sector solutions for when the public sector fails to act.

Meanwhile, last Tuesday I attended a webinar on blended finance — a technique for using philanthropic capital to reduce the risk levels for conventional impact investment: a rather complex process set out by the Canadian company ‘Convergence’, but at least an initiative which provides a set of private sector solutions for when the public sector fails to act.

Our own, much simpler, plan for ‘Shares/Stock for Data’ as described in our commentary on 21 February would be a comprehensive and international solution for sharing the immense wealth generation from giant tech companies across all their customers.

Is HM Treasury exploring a strategy for sharing? I suspect not, at present.

The main reason why the welfare state has become such a huge burden in western democracies is the application of universal, as opposed to targeted, benefits. Our commentary back on 30 October 2017 tackled this challenge, which has evolved from a combination of socialist universalism and electoral giveaways over the past 70 years.

The burden of these arrangements falls squarely on the shoulders of future generations, not only in terms of national debt but also as a result of their own student loan repayment obligations — where the Chancellor’s plans (not mentioned in his speech) to extend the payback period to 40 years and lower the salary at which repayments must start will bring HM Treasury an additional £35 billion over the next five years.

The fact is that for most people making provision for their own healthcare and educational needs would comprise a reasonable set of life choices of how to spend their money, leaving the Government to pick up the tab for those who really need a safety net. Unfortunately, there is no longer such an offer from any centre-right political movement.

We do, however, have to develop a strategy for sharing, as the current position is morally unsustainable.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio