“We are walking a very tight line between tackling inflation and the output effects of the real income shock, and the risk that that could create a recession and push us too far down in terms of inflation.”

Andrew Bailey, Governor Bank of England

After decades of inaction on interest rates, and experimentation with quantitative easing as a policy tool, central banks are facing real challenges to their interest rate strategy. The Bank of England's Governor Andrew Bailey took a bravely cautious line when speaking last week at the Peterson institute for International Economics in Washington (as our quotation from his speech shows), and currency markets rewarded that caution last Friday with a significant mark down for the British pound.

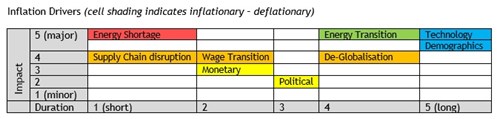

The range of major drivers which will steer inflation over the years ahead is wide and diverse, but their duration must be considered as well as their positive/negative impact on rates. For example, the drivers most affected by Putin's war in Ukraine are energy shortages and supply chain disruption, and the threat of de-globalisation in future. These all contribute to higher inflation but, unless the war pushes into 2023 – possible, according to Boris, but unlikely - it is only a more cautionary approach leading towards de-globalisation which will persist.

So in this commentary we take a look at nine major influences on future rates of inflation, and conclude that Andrew Bailey is probably correct in not over-reacting to the current turmoil.

This chart shows those nine major influences within axes showing the significance of their impact and the long or short term nature of their duration; and with cell shading to indicate their inflationary (red)/deflationary (blue-green) impact. These can also be interpreted within a more classical analysis of inflationary theory.

There are two overriding major influences, both of whose duration is long-term and which are both profoundly deflationary. These are technology and the digital economy, and demographics. The first has been the dominant feature driving rates downwards for the past two decades, and it will continue to do so well into the future: de-monetising demand and introducing huge scalability in supply. The second reflects the fact that ageing populations do not drive economic demand vigorously, as do young people.

The other two drivers with high degrees of influence are energy shortages and energy transition. The former may be intensively inflationary but it is a short-term feature. This is because cost inflation in fossil fuels will significantly accelerate transition to alternative energy, whose running costs will be much lower once the initial investment has been made. A very direct example of this is the Sahara Solar project Xlinks, which Ambrose Evans-Pritchard described graphically in his Telegraph Business article last Friday. He described it as the ‘ultra-cheap and renewable power poised to replace the OPEC-Russia system’; it’s also discussed in The Bigger Picture this week.

The threat of de-globalisation as a reaction to the supply chain disruption caused by international tensions was the central theme of our recent commentary on trade imbalances. Both de-globalisation and supply chain disruption result in higher prices, but the latter is likely to be resolved in relatively short order, as we're currently seeing with Brexit. Meanwhile competitive western markets will help to keep production costs in check, and a degree of de-globalisation is not therefore likely to result in major upward price pressures in the long term.

This leaves us with the political/fiscal/monetary drivers, and the risk that wage transition in the labour market could prolong the impact of rising inflation.

There is no doubt that politicians would like to inflate some of their massive public debt away, providing that it doesn't lead to excessive debt servicing costs as yields rise. The latter is less of a problem in the United Kingdom due to the high proportion of long maturity index-linked bonds: inflation itself is more of a threat. On balance, I would describe the duration of political influence as medium-term and relatively balanced in its impact - and no doubt that's why central bankers and finance ministers are taking a ‘wait and see’ attitude.

The challenge that higher inflation could persist as a result of wage transition in the labour market could push some of these short-term inflation pressures into the medium term. It is only sacrifice in standards of living which can hold that back, and unfortunately that particularly affects the most disadvantaged, who have little bargaining power to move wages and benefits. However where leverage is available, such as in the recent 8.6% wage settlement within Airbus Industries, it will extend the footprint of inflation into the future. It's worth bearing in mind, however, that trade unions don’t have anywhere near the bargaining power which they had forty years ago.

US CPI inflation was 7.9% in February, comprising energy (1.7%), food (1.1%), goods (2.5%), and services (2.6%), and that clearly wasn't yet reflecting the full impact of soaring oil and gas prices. However, if the transition to alternative energy is accelerated, and if the impact on wage inflation is restrained, Andrew Bailey's cautious optimism may be rewarded by what, in retrospect, may look like a temporary spike caused by Putin's war.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio