“If you remove the yoke from among you, the pointing of the finger, the speaking of evil, if you offer your food to the hungry and satisfy the needs of the afflicted, then your light shall rise in the darkness and your gloom be like the noonday.”

Isaiah 58: 9-10

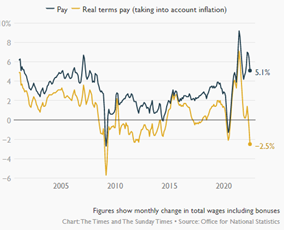

The ONS reports the sharpest fall in real wages since the financial crash, but is the pain of soaring inflation shared by all?

As the inflation rate has moved into double-digit territory for the first time in over forty years, there have been many comparisons drawn with that surge in inflation caused by Middle Eastern suppliers holding the world to ransom in the 1970s. Stock market reaction at that stage was dramatic: far worse than the weakness we've experienced over the past few months.

That contrast bears out the fact that there is little comparison with those days: and yet the massive increase in fossil fuel and food prices driven by Putin's war in Ukraine is every bit as severe as the oil price rise of the 1970s. So, notwithstanding the fact that economic recession is expected, why are stock markets so sanguine about the conditions facing us today?

The answer to that question is all about relative quality of life, as opposed to gross domestic product (GDP). It shows that, whereas stock markets can sense how quality of life is perceived by investors, there is no metric that economics can use to show us how to analyse the standard of living more generally. However, major price movements in stock markets speak only for the rich and powerful segments of society — the challenge is to enable all to share in the same satisfactory quality of life that stock markets are reporting for the wealthiest investors.

It was in April 2020 that we wrote of the inadequacy of GDP to assess the impact of the pandemic, and about the reason why the technological revolution had led to the extraordinary low interest rates that we have experienced for the past fourteen years. But it's not these ultra-low interest rates that have led to the current surge in inflation, it's the direct result of Putin seizing his last chance to hold the world to ransom while fossil fuels still hold their sway.

In a sense, however, he has already missed the boat: stock markets are showing that the new world order is already providing the rich and powerful with a very diminished exposure to his challenge. They are in large part working from home, driving electric cars and holding international meetings by Teams and Zoom in order to cut down on air travel.

Meanwhile those with collective power are flexing their industrial muscles: closing down the railways, shutting off the post and halting container traffic in order to make their case for higher wages to compensate for soaring food and fuel prices.

So, the standard of living is being addressed by these strata of society by means of adjusting their lifestyle or demanding higher pay to compensate for Putin’s outrage.

The problem is for those who do not have these luxuries or bargaining power, and for the young. Far from introducing a more egalitarian society as Marx and Lenin had decreed, the irony is that the inheritors of Russian communism are enforcing an ever-greater polarisation of wealth across the world, and at the same time inflicting a serious handicap on younger generations.

The problem is for those who do not have these luxuries or bargaining power, and for the young. Far from introducing a more egalitarian society as Marx and Lenin had decreed, the irony is that the inheritors of Russian communism are enforcing an ever-greater polarisation of wealth across the world, and at the same time inflicting a serious handicap on younger generations.

The young are hit particularly hard because:

- they have no bargaining power with which to demand higher incomes;

- they need to learn about business and enterprise from those who currently hold the reins — but they cannot do so when so many of these older more experienced people are working from home or meeting virtually;

- it is all but impossible to buy property when faced with sky-high prices, swiftly rising mortgage rates and being saddled with student debt; and

- the birth rate is so much higher among the disadvantaged and ethnic minorities and they are therefore trapped by the cycle of deprivation.

We've heard a lot about restarting growth, and there has been much debate about hand-outs in the Conservative leadership election which comes to a head next week. Growth may well encourage the stock market, and it will no doubt further enrich the powerful. Meanwhile hand-outs will, as with all grant giving, ‘feed for a week’; but they will not teach the disadvantaged how to feed the families for a lifetime.

That's why I wrote to both leadership contenders a month ago to seek their views on introducing a more egalitarian form of capitalism, following the principles set out in our commentary on 9th May. I have not received a reply from either Liz Truss or Rishi Sunak: not an encouraging start to the new Conservative administration, whoever ends up in 10 Downing Street.

After over thirty years of trying to encourage profit-centred commerce and short-term governments to tackle the most intractable economic problem experienced by humanity — the intense polarisation of wealth — it is increasingly clear that only the development of real academic rigour, communicating the need for change, followed by a broad global coalition of people committed to a new strategy to resolve the way forward, will enable quality of life and proper standards of living to be shared by the young and disadvantaged, as well as the rich and powerful.

Determination, not despair, is needed to provide and maintain quality of life for all.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio