“Long-term economic growth depends mainly on non-monetary factors such as population growth and workforce participation, the skills and aptitudes of our workforce, the tools at their disposal, and the pace of technological advance. Fiscal and regulatory policies can have important effects on these factors.”

Jerome Powell, Chair of Federal Reserve

Last Friday’s so-called mini-Budget is tightly focused on production and finance — the supply side of the economy. The small gestures in respect of demand, such as 1p off the basic rate of income tax, are little more than window-dressing, especially bearing in mind mortgage rate rises driven by the Bank of England's 0.5% hike in rates last week — with more to come in due course.

Meanwhile, for those worried about the fall in the exchange rate, I suspect that is all part of the strategy to pile on incentives for exporting (and corresponding penalties for importing), although I’m sure parity with the dollar isn’t part of the plan. Meanwhile those energy cost reliefs are supposed to provide a degree of protection against dollar-denominated fossil fuel pricing, but that will also be less effective if the pound sinks much lower.

Production and financial services are undoubtedly the targets for the Chancellor's growth strategy — we are no longer to be a ‘nation of shopkeepers’, and that is a sound judgement to make. Shopkeepers are now global and online: they don't need the United Kingdom as a working base.

However, there is one key missing link in Kwasi Kwarteng's Growth Plan — workforce capacity. He's tried to address it to a limited degree by incentivising mobility, in slashing stamp duty on the average property purchase. But it doesn't tackle the harsh fact that the unemployment rate is already at a record low of 3.6% (the lowest rate since 1974), with many more vacancies than job-seekers: and, unless the economy goes into freefall (precisely what Mr Kwarteng says he doesn’t want), it's simply not possible to conjure people up out of nothing, particularly when so many Europeans have left following Brexit.

Meanwhile, although the Sunday Times headlined ‘Truss’s plan for more migrants to boost growth’, it also reported significant opposition from her new cabinet, quoting a senior government source as saying ‘We cannot tear up our immigration rules. People who voted for Brexit want to see controlled migration’.

But — if we don’t tackle workplace capacity, the Growth Plan won’t work: a new determined approach is therefore required to tackle the need for more people prepared to work.

Last week, our commentary focused on energy as the third element to be added to the traditional economists’ duality of capital and labour; this week, the need for more people at work glares out from between the pages of the Growth Plan. The Chancellor has done much to encourage capital to flow with major initiatives for financial services, but without workforce capacity his plans will only fire up those parts of the economy which do not employ many people. For his strategy to be really effective, we need more people to produce more output for export, hauling back those swathes of productive capacity which in recent decades have gone to the Far East.

In order to do this, we must open up employment prospects for both young and old, and this requires a new strategic focus to accompany the Chancellor's growth strategy.

For young people aged 16-24, the unemployment rate in the three months to July 2022 was 9.1%, much higher than the national average of 3.6%. There are several reasons for this, including lack of experience, lack of mobility (the high cost of housing means that a high proportion continue to live in their childhood home), and lack of life skills.

At Share Radio and The Share Foundation we have been asking for a coherent strategy of inter-generational rebalancing for several years, incorporating a much more pro-active effort both to link starter capital accounts (Child Trust Funds) to their young adult owners and to introduce a programme of incentivised learning designed to provide life skills for those from lower-income households. Our comprehensive proposals were detailed on 7th February, and The Share Foundation has been leading a programme of CTF recovery for the past four years. There are now over one million young adults with unclaimed accounts worth nearly £1.5 billion: almost all from low-income households.

We have also pressed regularly for a Financial Awareness GCSE in order to require a greater focus on financial education in schools: only 25% of those leaving school consider themselves adequately prepared for adult life, and therefore for the workplace. In this respect it’s encouraging to see that the Personal Finance Society has just teamed up with the Duke of Edinburgh Awards programme to expand access to its financial education programme.

Office for National Statistics figures show that young people’s inactivity rate is much higher for those from work-less households, illustrating the huge benefits to be achieved by helping young adults’ mobility by them claiming their Child Trust Funds. Meanwhile the incentivised life skills learning programme which we have proposed would do much to help prepare them for work, and to build their experience.

At the other end of the age scale, the challenge is to keep people available for work longer. The key challenges here are very different to those for young people. They need to maintain a good standard of mental and physical fitness for work, and there would be an additional substantial benefit for the public sector in a corresponding reduction in the costs of health and care services.

Preparing young people for adulthood involves 12-15 years of training in school and further education; in contrast there is virtually no training to prepare people for life beyond 65. We need to introduce a comprehensive programme to teach people how to stay fit and healthy in old age, and to encourage them to stay active and productive in working environments of their choice for as long as possible. This training programme could also be incentivised (although it's likely that most older folk would understand the benefits of taking part without the need for reward).

The combination of these two initiatives, at both ends of the working age-range, should increase the available workforce by at least half a million people, together with significantly improving mobility for young adults so that they can take advantage of work opportunities wherever they arise.

The Government should therefore take urgent action to increase capacity in the labour market in this way, in order to enable their growth strategy to be achieved.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio

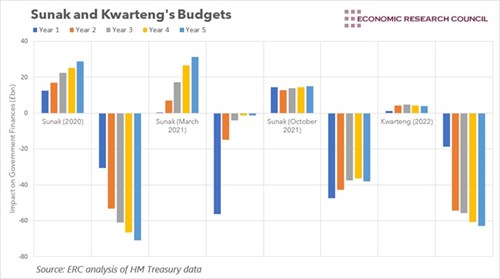

This Economic Research Council chart shows the projected impact of recent budgets (along with Kwasi Kwarteng’s “mini-budget”) on Government finances. The financial impact is shown for the five years following the budget and is split between policies that add to (above the 0 line) or detract (below the 0 line) from Government finances. Each budget is identified by the Chancellor who delivered it, with policies increasing finances above their name, and those detracting from finance to the right of their name. The chart does not include any announcements made before each budget. All values are in £ billions.