“Capitalism is not a form of government. Capitalism is a symptom of freedom. It is the result of individual rights, which include property rights.”

A.E. Samaan, Investigative Historian & Author

The headline on a double-page spread in the Times on Friday 10 June was ‘Johnson hopes first-time buyers hold the keys to keeping No 10’, and it included an OECD chart (right-hand column) showing how home ownership and renting compares in a range of countries. In the UK, at 65%, we've certainly slipped a long way from the focus on ‘right to buy’ and popular capitalism over the decades since Margaret Thatcher was in power.

Politicians often speak glibly about ownership as if it's a definitive term, but the sense of ownership depends on a whole range of features. In the long term we are all only stewards of what we own, as we can't take it with us when we go. But the reality of ownership still relies on some influential characteristics including the extent to which it offers us participation and the ability to control our assets, and the degree to which it carries with it a sense of responsibility.

So in this commentary we look at a number of different styles of ownership, and how they weaken or strengthen that sense of connection for which Boris Johnson is no doubt seeking.

Property ownership - real estate - is, of course, severely challenged by debt, and almost two decades of easy borrowing at rock-bottom interest rates really hasn't helped. Bankers and finance companies have strained to maximise loan availability, to the extent of exceeding 100% through ‘shared ownership’: but when you're in hock to the bank to such a colossal extent, do you really get a sense of ownership, or does it just pile on anxiety?

Leverage is a key problem which we must solve in order to relieve the stress that can accompany super-size mortgages; and although some property professionals might try and portray the alternative of leaseholds as ‘ownership’, they are, of course, no such thing — particularly if they’re short duration.

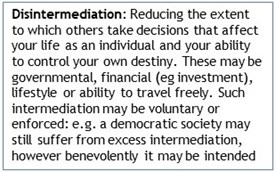

Then there's excess intermediation. Of course many people choose to pass control of their investments over to others, often because they don't have the time, the confidence or the knowledge to manage them directly. But stepping away from control should be a conscious decision by the owner, not an imposed decision which obscures access and transparency so that others can wield power. In financial services there are far too many examples of excess intermediation — fund management, pensions, life insurance, etc.. — and the absence of proper financial education simply exacerbates the process of keeping people in the dark about their own investments.

Then there's excess intermediation. Of course many people choose to pass control of their investments over to others, often because they don't have the time, the confidence or the knowledge to manage them directly. But stepping away from control should be a conscious decision by the owner, not an imposed decision which obscures access and transparency so that others can wield power. In financial services there are far too many examples of excess intermediation — fund management, pensions, life insurance, etc.. — and the absence of proper financial education simply exacerbates the process of keeping people in the dark about their own investments.

These examples should not be confused with custodial administration using ‘bare trustees’. Advocates of registered share ownership often try to present this as intermediation, but it's nothing of the sort: rather, it enables the service organisation to be the owner’s agent rather than the agent of the stock-issuing corporate, and it helps to develop investment awareness, as a share portfolio builds and diversifies. It must, of course, be accompanied by full opportunity to exercise shareholder engagement: this process started in the UK with Companies Act 2006 Part 9, but it needs further strengthening.

Indeed — when ‘Stock for Data’, discussed in our commentary on 21 February 2022, is introduced, it may well be on a custodial administration basis in order to provide a straightforward route to global coverage.

Widespread stock ownership is a key objective for moving to a more egalitarian form of capitalism, which includes the provision of financial awareness life skills to help build capability for looking after the asset and the income and its potential capital gain, and the risks associated with asset ownership. Please refer to our proposals for egalitarian capitalism for more details.

True ownership involves control and possession of the asset, whether it be property or stock: that means retaining the ability to crystallise its value. There are many examples of participation which don't do this: in particular, co-operatives and mutuals speak of participation, but only while the individual remains an employee or a member. Businesses such as the John Lewis Partnership, building societies and friendly societies are typical examples of this: they present themselves as inclusive, but there is no monetary value in the participation of a capital nature.

It's for these reasons that ‘Stock for Data’ refers to stock issuance in return for data storage and harvesting, and the (disposable) stockholding should increase as the relationship moves forward from year to year. As evidence emerges of Apple expanding its strategy for monetising data (Sunday Times Business section, 12 June), the role for ‘Stock for Data’ will continue to increase, if tech giants are to avoid anti-trust break-up.

Finally of course, ownership in any society is only as good as its recognition in law. Western democracies have centuries of experience in building property rights into their constitutions, and no doubt this is one of the key reasons why London has attracted so much investment over the years. But there are so many examples of property rights being trampled on, whether by political systems, by government dictact or unfair taxation, or by outright theft and destruction — as in Putin's war in Ukraine.

If people are to have confidence in a sense of ownership and to build the responsibility that it engenders, they must know that acceptance of their property rights is sacrosant — and this confidence must extend globally. There is a lot to do in this respect.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio