“Shareholder activism is not a privilege — it is a right and a responsibility. When we invest in a company, we own part of that company and we are partly responsible for how that company progresses. If we believe there is something going wrong with the company, then we, as shareholders, must become active and vocal.”

Mark Mobius, Emerging Markets Fund Manager

Next week, if there are sufficient ministers in HM Treasury to welcome its publication, the Austin report will be released. This is a major review of the London securities market designed to increase its appeal for companies raising capital — and, hopefully, for personal investors.

At this stage of high inflation and rising interest rates, stock markets — which are primarily moved by anticipation rather than actual demand and supply — have already taken fright. In contrast, property markets, whose motivation is the reverse, are still touching new highs: although the rate of price acceleration has markedly slowed over recent months.

However personal share ownership needs rather more than Mark Austin's supportive comments. This week we look at three key improvements where change is urgently required in order to recognise the major contribution that ownership, rather than trading, can bring in delivering participation in wealth creation for all.

It is the link between ownership and responsibility which first attracted me to direct personal investment in shares nearly fifty years ago. When someone owns something, be it a house or a car, they generally care for it. If it's a house, the walls are painted, the garden brims with flowers; if it's a car, it's generally clean and well maintained.

So it is with owning shares in a company. Every time an M&S share owner walks into Marks and Spencer, they feel a buzz of responsibility for the way it's run. Meanwhile, if customer share owners are recognised with special offers or discounts, that sense of connection is strengthened further.

The media focuses so often on share-dealing and short-term price movements, but most investors are long-term holders, They are not day-traders or gamblers: they’ve invested for long-term growth accompanied by, where available, a regular flow of dividends.

But share ownership and enfranchisement is not adequately recognised in the United Kingdom, or indeed in many countries across the free world.

For example, the most suitable vehicle for building a share portfolio is with a retail investment business, with the shares themselves held in that company’s bare trustee nominee company: but although we made huge strides with enfranchising nominee share owners in the Companies Act 2006, we urgently need to make the supply of company communications and voting rights mandatory for all such regulated nominees.

Another key feature of participation is the right, together with other share owners, to circularise others who own the shares, and to bring forward resolutions for consideration at a General Meeting. However, company law still sets the threshold for this participation by reference to the nominal value of the shares, which bears no relevance whatsoever to their market value. So, whereas in one company the threshold may be measured in £millions, in others it could be a few pounds. I asked lawyers for the Department of Trade to address this in 2006, only to be advised that they couldn't accommodate the change — ‘come back in twenty years’ time for the next revision of company law’! Well that's only four years away now ..

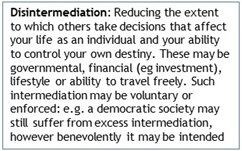

A further major handicap for the genre of personal share owners in a listed company is that every time there is a rights issue, raising more capital from existing share owners, the proportion of personal investors holding the stock reduces sharply. Institutional investors strengthen their position, and financial intermediation turns the screw a little harder.

A further major handicap for the genre of personal share owners in a listed company is that every time there is a rights issue, raising more capital from existing share owners, the proportion of personal investors holding the stock reduces sharply. Institutional investors strengthen their position, and financial intermediation turns the screw a little harder.

This is because, for institutions the ‘old’ and the ‘new’ money are held by the same entity — so pre-emption rights work in their favour. But for personal investors, the ‘old’ money belongs primarily to those who are disinvesting in old age: they have no ‘new’ money to take up the nil-paid rights. However personal investors who do have that ‘new’ money but don't hold the ‘old’ shares are excluded from taking part by those same pre-emption rights.

In order to address this, it should be mandatory for the rump sell-off of nil-paid rights at the end of the ‘Call’ period to be offered to all personal investors (via their retail investment service), alongside the institutions. At least this would help reduce the dilution in personal investor holdings in listed companies every time they carry out a secondary capital raising via a rights issue.

These three changes alone would significantly raise the profile of personal share ownership — but will they be included in Mark Austin’s review? They are significant steps forward in moving to a more egalitarian form of capitalism, in which share owner engagement and protection against systemic dilution are key features. None of these three proposals would incur cost to the public purse and, if leadership contenders for the Conservative Party really believe in key Thatcherite concepts of popular capitalism — as they claim to — they should jump to make them happen.

There is, of course, another major difference between personal share ownership and home ownership: the former offers participation in wealth creation which is central to eliminating the ‘us and them’ division in society, again starting to rear its ugly head as the cost of living crisis bites and the more powerful employee unions bring in a wave of strike action.

A broad and global spread of personal share ownership could be introduced via ‘Stock/Shares for Data’, and a steady transition to this egalitarian capitalism concept could play a major role in avoiding a subservient, welfare structure such as that offered by Universal Basic Income. It is only by sharing capital growth and the flow of dividend income across society that we will achieve individual empowerment for all.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio