“I sincerely believe that banking establishments are more dangerous than standing armies, and that the principle of spending money to be paid by posterity, under the name of funding, is but swindling futurity on a large scale.”

Thomas Jefferson

The past seventy years have seen remarkable progress in so many areas, but they have also been accompanied by a growing addiction to debt. For the public sector, it's an international scourge and it is extraordinary that, even with the UK national debt now standing at 86% of GDP, Liz Truss is able to claim the second lowest Debt to GDP ratio in the G7. It's an awful indictment of democratic capitalism as we currently operate it that we leave such a massive burden for our children and grandchildren to shoulder in the decades to come.

So it's good to hear that the Chancellor's plans for controlling his debt-building deficit are now being brought forward to the end of this month, following the market reaction over the past fortnight.

The 2008 financial crash blew a massive hole in corporate debt in 2009, resulting in a huge transfer to the public sector in order to save the banking system. However, the personal sector has continued to borrow at a massive rate as interest rates fell to unprecedented lows, and the Economic Research Council has now laid bare the crisis facing personal disposable incomes and the UK property market.

The truth is that we have lost connection with the disciplines which should govern the use of debt. A bit like the road runner who has just lost touch with the cliff edge, there is no longer any solid ground on which we can land: so anticipate a painful re-adjustment as markets fall.

I recall a Capital Economics seminar at which the transfer of huge quantities of corporate debt to the public sector was discussed, shortly after the banking bail-out which followed twenty years of excess leverage in the financial system. In my view, and as I discussed with market-maker Brian Winterflood on 9th December 2014, this was directly related to the introduction of dual capacity; the process whereby the roles of principal and agent became hopelessly entangled. Since the financial crash, business has been much more disciplined in its use of debt, assisted by much tougher regulation.

The personal sector adjustments at that time were comparatively minor, and house prices continued to soar in value as interest rates collapsed to unprecedented levels. In a world in which supply was boosted by technology and global mobility while, in so many areas, demand became virtual and was de-monetised as a result of online access, traditional monetary economics had to fight hard to stop deflation taking hold. As interest rates fell, so also did anticipated returns — therefore pushing asset prices ever higher.

The main beneficiary, however, was property prices — not stock markets, which have remained broadly stable over the past twenty years, apart from a sudden plunge and recovery during the financial crisis itself. Lower interest rates and increased ‘loan-to-value’ ratios pushed up the prices that home-buyers were prepared to pay. The scope for major shocks as a result of a return to traditional interest rates therefore became higher year-by-year.

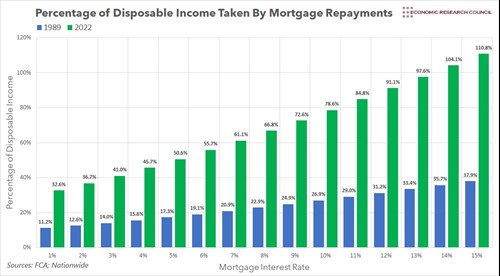

The Economic Research Council has laid this out in graphic detail in their report on mortgage repayments as a percentage of disposable income. They show how, far from entering a period of growth as Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng want, intense pressure on the nearly seven million households in the United Kingdom who own their property with a mortgage has the potential to grind consumption to a halt.

Image Source: Economic Research Council

Average house prices have risen from £60,700 in 1989 to £282,800 today, a rise of over 450% over the past 33 years. We have already drawn attention to the devastating impact of this on young adults, as the average age of first-time home-ownership approaches 40. But it also means that, for an 80% loan-to-value, the mortgage on the average house value is £226,240. An additional 5% in interest charges would therefore incur £11,000 pa.

The property market is therefore bracing itself for a significant fall in prices, and hopefully this will in due course enable young people to think more positively about buying their own home. It won't, however, do much for the mainstream support for the Conservative Party.

Government must also re-think its way out of using debt as the first port-of-call in times of trouble. The cost of their bonds is now heavily scarred by increases in both inflation and interest. Index-linked bonds, first introduced in the 1980s, were originally intended to confirm the resolve of Government to get inflation under control: but they are now hugely expensive. Meanwhile the fixed-coupon ‘Gilt’ market is also presenting colossal financing costs.

So, we are now hearing more about getting public spending under control in the debate about benefits: something which the Labour Party also clearly doesn't understand following their comments about simply using the now re-introduced 45% tax-rate for higher earners to increase spending on the NHS.

The fundamental problem with escalation of peace-time public debt started after WW2, with the introduction of the welfare state. Instead of targeting support where it was really needed, the socialist mantra of free health and education for all have become a universal bribe for all political parties in order to keep voters onside. It has therefore driven the massive rise in debt, while at the same time depleting the resources available for safety-net provision.

If we want to get public debt under control, we must tackle the universal provision of services to all. We must give people more choice and encourage them to pay for these services where they can afford to do so.

Over-extended debt has taken decades to reach these ridiculous levels, and weaning ourselves off it will not happen overnight. But we need to move to a mindset where debt is a form of investment for the future, to be drawn down carefully and sparingly — not to be used either for chasing higher and higher prices, or for incessant Government bail-outs.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio