‘What is education without a better economic growth?’

Lailah Gifty Akita, Author

We'll be hearing a lot about the ambitions for growth in the UK economy this week. The Chancellor will major on it in Wednesday's Autumn Statement, and the Opposition will join the chorus — but if you reckon that the swiftly-building headroom in public finances will enable it all to happen, think again.

There are two factors generating the turn-around in public finances: the forcing of large numbers of ordinary working people into higher tax rates as a result of frozen tax thresholds, and the sudden and dramatic reduction in the inflation rate as the price of energy has fallen. This has brought real hope to the bond markets, not only reducing the immediate cost of Government borrowing but, far more significantly, slashing the contingent liability cost of HM Treasury's obligation to indemnify the Bank of England when it sells off those bonds bought at very low interest rates during the pandemic. This contingent liability has been more than £150 billion — watch carefully as it falls.

There will, therefore, be no shortage of capital to spur growth, either from the public sector or from investment markets; the latter as investors take profits on their bond holdings and re-invest into equities. And, if further incentives are built into ISAs to encourage people to purchase UK shares, there’ll be still more capital available.

The problem, however, is labour: and if the Chancellor thinks he can force increased capacity by reducing benefits, he’ll not only fail to achieve that result but will also lose still more votes in next year’s critical election.

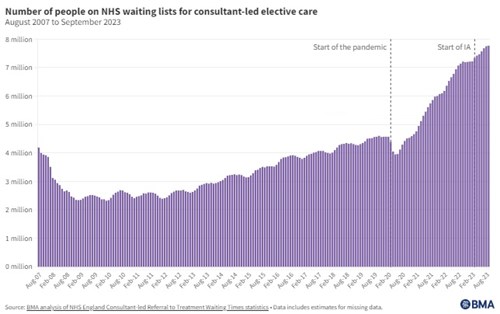

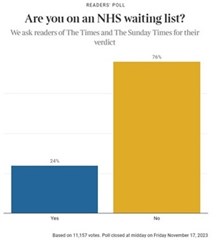

The biggest stranglehold on working capacity in the United Kingdom is the state of its National Health Service, where Jeremy Hunt was the longest-ever serving Health Secretary before becoming Chancellor. The current NHS waiting list of over 7.5 million people is not imaginary — it's a reality, and it's stopping people from working. In a survey of over 11,000 people, yesterday's Sunday Times reported that 24% of respondents were on NHS waiting lists (image: Sunday Times).

The biggest stranglehold on working capacity in the United Kingdom is the state of its National Health Service, where Jeremy Hunt was the longest-ever serving Health Secretary before becoming Chancellor. The current NHS waiting list of over 7.5 million people is not imaginary — it's a reality, and it's stopping people from working. In a survey of over 11,000 people, yesterday's Sunday Times reported that 24% of respondents were on NHS waiting lists (image: Sunday Times).

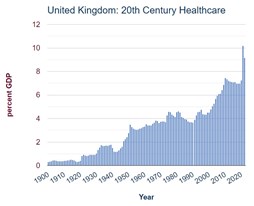

Our health service is thoroughly dysfunctional, and it's not just the fault of thirteen years of Conservative-led administrations (remember that for five of those years the Liberal Democrats shared responsibility, in the Coalition government). The greatest challenge is the legacy of nearly seventy-five years of state monopoly: the total absence of competition has made the whole process very inefficient and very expensive.

So, when a shock like the pandemic hits, there's no capacity to respond other than becoming even less efficient. And when inflation calls for higher wages, there's no defence such as the availability of competitor services to restrain the workforce from walking out.

Monopoly state health provision is a Labour Party construct which, for decades, Conservative administrations have been too frightened to challenge: but it must be challenged. No-one questions the care and public service motives of those working in the NHS, but its gargantuan appetite for cash and the lack of competitive challenge has resulted in its dysfunctionality.

Monopoly state health provision is a Labour Party construct which, for decades, Conservative administrations have been too frightened to challenge: but it must be challenged. No-one questions the care and public service motives of those working in the NHS, but its gargantuan appetite for cash and the lack of competitive challenge has resulted in its dysfunctionality.

This will take time to address, but a start could be made by requiring wealthy old folk to have mandatory private health insurance which could be drawn down as they use NHS services. There also needs to be an open door to sharing medical records with the private sector, so that its capacity can be accessed more easily. Then, gradually, we need to start moving away from the mantra of ‘free at the point of use’. That doesn't apply to dentistry now, and it shouldn't apply for those well able to afford their own healthcare.

Of course, there need to be free health services targeted for those unable to pay, but socialist blanket welfare provision has proved to be wholly unsustainable.

There also needs to be training for people of all ages on how to take more care of their own health. Joint replacement, in particular, has reached an almost industrial scale and is responsible for a very significant number of those unable to work. However, this could be substantially alleviated by training programmes for daily stretching exercises supplemented by herbal diet supplements such as turmeric or collagen.

Labour shortages are not, however, just due to our grossly ineffective health service. The focus on university higher education which has applied for the last twenty years also has much to answer for, as it's left skill shortages in many areas which are key to holding back economic growth.

Take, for instance, the urgent need to convert housing for zero-carbon energy. The technology is all there for making this change, using air source heat pumps and much improved insulation. However, there is a woeful lack of engineers able to fit this equipment, notwithstanding significant demand from both private and public sectors

The recent emphasis on apprenticeships will help substantially, but it takes time to build up proficiency. There needs to be more encouragement and incentives to raise the profile and recognition of work such as this.

Within a few hours of publication of this commentary, the Chancellor will set out his proposals, and no doubt we’ll see a strong focus on appeal to the electorate and on investment, which may boost the London stock market. We may see some reform of inheritance tax along the lines that we proposed on 5th June, but I doubt if there'll be any radically new proposals for health service funding. Meanwhile any moves to ease income tax pressures will probably not take effect until April ‘24.

The central problem for the UK economy is likely to remain: an excessive reliance on Government control and provision and very short-term thinking. Until the structure of government is reformed to provide reliable oversight from a long-term perspective, as we called for on 9th May, the problem of lacklustre growth will remain.

So please enjoy this week's media coverage of Jeremy Hunt's plan for the immediate future — we'll be providing his full speech as a podcast later in the week — but you'll need to watch very closely to see any indication of more strategic thinking. My guess is, that will be hard to find.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio