‘Times have been tough, the economy has been tough. But I want to bring forward a fantastic manifesto for taking the city forwards.’

Boris Johnson

As 2024 gathers momentum towards the next UK general election, there will be scores of political advisors and pundits working on their party manifestos, just as Boris planned in preparation for his eight years as Mayor of London. As the financial crisis (to which he referred) loomed sixteen years ago, it was easier to nail colours to the respective parties’ masts: these days, the electorate would be justified in detecting opportunism taking the place of underlying principles.

One of the Glasgow audience for last Thursday's BBC Question Time rightly set out the major economic challenge confronting our system of democracy: all parties have contributed to building such a mass of debt that there is little scope remaining for further government commitments, in any direction. His point was borne out by the International Monetary Fund, which warned Britain against cutting taxes in the forthcoming Budget on 6th March.

It's all due to short-termism and, if Mr. Sunak really wants to take ‘long-term decisions for a brighter future’, he should read our commentary.

You have to start with basic principles, and the old party mantras of the right (so-called freedom, while the rich get richer and the poor, poorer) and the left (state monopoly provision born out of socialism) simply don't work anymore. We need a new set of principles for a fast-changing world, and it would be hard to improve on these:

- A deep respect for others, from all backgrounds and however different they may be;

- Seeking out long-term, and particularly inter-generational, methods for a more egalitarian sharing of individual wealth and participation in wealth creation; and

- A strong commitment to disintermediation — individual freedom and self-control (provided, of course, that it doesn’t undermine that essential respect for others and their interests).

This combination doesn't fit any of the current political parties jostling for power. None of them really understands that individual freedom is more important than government dictat, and those who believe in a more egalitarian society always think it has to be imposed — how wrong they are, it has to be enabled, not imposed.

This combination doesn't fit any of the current political parties jostling for power. None of them really understands that individual freedom is more important than government dictat, and those who believe in a more egalitarian society always think it has to be imposed — how wrong they are, it has to be enabled, not imposed.

There was an interesting comment piece in The Times last Saturday headlined ‘Tory right has never understood freedom’, but its author Matthew Parris clearly doesn’t understand it either: freedom of choice relies on having the resources and life skills which enable its exercise, and these are denied to the great majority of young people. Meanwhile the ‘Nanny State’ which he seeks to defend is only a very small part of the issue.

So it means looking intelligently at the different stages of life and at the human life cycle, and acting accordingly. It means delivering individual opportunity for disadvantaged young people (what we describe as inter-generational rebalancing), delivering choice and competition in the provision of essential services, and it means resisting the temptation to bribe the elderly with free, but desperately inefficient, universal health and social care. In this context, it’s essential to provide a proper safety net for those who really need it, rather than squandering public resources on universality.

So, what might this look like for specific departmental areas?

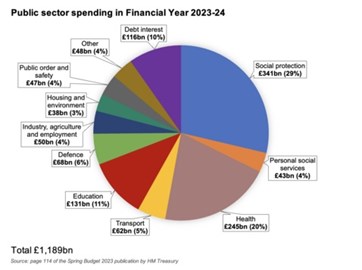

Health and Social Services simply cannot continue to consume such a vast proportion of public spending (53% in 2023-24). Wealthy old people should be required to have private insurance on which the NHS and social services can draw when they use it. There should be an open door to a choice of services, and a proper sharing of medical records (subject, of course, to individual consent); this is one of the key recommendations in The Times Health Commission, published on 5th February). These records should be shared with generally available (i.e. ‘private sector’) competing health services, so that the burden of health and social care can be gradually shared between a range of providers. This would also keep the impact of industrial action under control.

Health and Social Services simply cannot continue to consume such a vast proportion of public spending (53% in 2023-24). Wealthy old people should be required to have private insurance on which the NHS and social services can draw when they use it. There should be an open door to a choice of services, and a proper sharing of medical records (subject, of course, to individual consent); this is one of the key recommendations in The Times Health Commission, published on 5th February). These records should be shared with generally available (i.e. ‘private sector’) competing health services, so that the burden of health and social care can be gradually shared between a range of providers. This would also keep the impact of industrial action under control.

It is unacceptable that 10% of public spending goes on interest, reflecting decades of political over-indulgence. Debt has to be brought under control: but once the economic benefits of this transition away from universality flow into the public purse, HM Treasury should prioritise two key fiscal provisions as the public finances improve — lifting the freeze on tax thresholds as soon as possible, and hypothecating the proceeds of inheritance tax (note: NOT abolishing it) in order to provide starter capital accounts combined with incentivised life skills learning for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds. There also needs to be a real commitment to ensure that the £2 billion worth of unclaimed, adult-owned Child Trust Funds do reach the young people to whom they belong.

Wealth creation as a result of data harvesting and generative Artificial Intelligence should move in the direction of participation for all. Regulation should therefore be focused on the proposition of ‘Stock for Data’, and there should be a review of outdated copyright legislation to ensure that technological development and mass participation are not held back by intermediary and media interests.

Instead of just building barriers against migration, the Home Office and Foreign Office should look at what can be done for countries of origin in order to provide improved opportunity and peaceful living. Working with international media companies and businesses, we should encourage internationalisation via overseas apprenticeships and incentivised learning, and work directly with the United Nations in order to build stronger global governance, based on long-term policies. This should envisage the development of an international police force to deal with crimes such as the Hamas atrocities, rather than focusing on increasing national military forces.

Here in the UK we need to take a close look at how family fragmentation and limited social interaction is not only resulting in mental instability and loneliness but also driving an excessive demand for property: thus denying so many young people the chance to have their own accommodation and start building a family.

‘Respect for others’ should encourage widespread involvement in community action and, rather than introduce national conscription, young people should be encouraged to help in food banks, to care for the elderly and to engage in other support activities to build their sense of responsibility and social relationships.

In a five-year electoral cycle, the executive part of government will always err on the side of short-termism, and it's therefore high time that the second chamber is restructured for the specific purpose of reviewing the suitability of legislation for the long-term, and for providing a home for proposals focused thereon. People are well able to elect on this basis, and there should be a planned transition for the majority of the second chamber to be elected over the next ten years.

Finally, we must develop an appreciation for placing a premium, not a discount, on the lives of our children and grandchildren. As climate change and international conflict have shown us, humanity's impact on the future has risen exponentially over the past two hundred years. If our species — and many other species in our world — are to survive even a small fraction of the lifespan of the dinosaurs, we must stop making international comparisons in order to justify drilling for oil, and instead start providing an example for other countries on how to reverse global warming.

Whatever specific policies may appear in manifestos, they must start with setting out their principles clearly. The political spectrum is currently highly distorted towards self-interest and excess intermediation: let's hope that 2024 will see a move towards participation for all and individual opportunity.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio