Is the NHS the Elephant in the Room that no-one dare address?

At the Bennett Institute for Public Policy conference in Cambridge last Friday, the third session was called ‘Resilience — What do our institutions need to do to make the UK more resilient?’ The speakers included Catherine Little, who in April will take on the role of Civil Service Chief Operating Officer and Permanent Secretary to the Cabinet Office, following four years at HM Treasury.

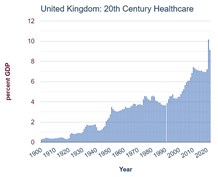

Listeners will recall my interest in finding a proper, long-term resolution for the NHS: our commentary called ‘Health and the Economy’ set out the challenge on 17th October 2022.

So I asked what could be done to resolve the situation. The Civil Service is clearly focused on the need to resolve the challenge — Cat Little answered my question very directly, saying, ‘the new government [that is, post General Election] must tackle this head on’.

The real dilemma is political, however. It would help greatly to facilitate her determination to tackle this key issue if the two main parties were prepared to admit to their very different handicaps, and if they were to agree a consensus for moving forward.

My question for the Bennett Institute Resilience panel set out the dilemma. I drew attention to the manner in which universal monopoly provision of ‘free at the point of use’ health provision had lost its resilience, as its demands on public expenditure have soared while its efficiency and productivity has collapsed. The ‘Mexican Stand-off’ reference in the title of our commentary reflects the challenge of having the Labour Party grounded in socialist dogma, while the Conservatives are too scared to require wealthy old folk to pay for their health service needs due to the real prospect of losing voting support amongst their mainly elderly support base.

My question for the Bennett Institute Resilience panel set out the dilemma. I drew attention to the manner in which universal monopoly provision of ‘free at the point of use’ health provision had lost its resilience, as its demands on public expenditure have soared while its efficiency and productivity has collapsed. The ‘Mexican Stand-off’ reference in the title of our commentary reflects the challenge of having the Labour Party grounded in socialist dogma, while the Conservatives are too scared to require wealthy old folk to pay for their health service needs due to the real prospect of losing voting support amongst their mainly elderly support base.

That last point was borne out in discussion after the session with a former Minister, who cited the dire consequences this had provoked when it was included in their 2001 election manifesto. Painful memories last a long time, and this may also explain why Jeremy Hunt is so resolved to keep the 'triple lock' on state pension increases in the Conservative manifesto.

However, there is likewise no indication that Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves is about to dispense with socialist dogma as the bedrock of the welfare system. The Mais lecture which she delivered in the City of London on Tuesday 19th March has drawn mixed reviews:

- The New Statesman spoke highly of the talk, describing it as ‘Bidenism comes to Britain’ in its editorial; and claiming that Rachel Reeves ‘aspires to nothing less than the establishment of a new economic consensus’ — like Margaret Thatcher, but this time from the left, rather than the Hayekian right.

- However Matthew Parris, writing in The Times on Saturday 23rd March, described the same speech as ‘Reeves’s shapeless wordfest is a true shocker’: that she repeatedly hedged her statements so that there was ‘no evidence of the evangelism that can carry governments to a place in history’.

The heart of the problem is that socialism is a busted flush, as we said a couple of weeks ago. Instead of universal welfare systems, we need targeted support for those who need it most. Meanwhile, if we really want to tackle the intense polarisation of wealth, we must do so by introducing a more egalitarian form of capitalism, not socialism, and this needs to include a constitutionally based system of inter-generational rebalancing.

The absence of a way forward is due to having the two main parties competing for the votes of old people, and viewing their free health and social care as an electoral bribe. However, the crisis in health and social care funding is so serious that it cannot remain a subject of political football. The situation calls for an agreed cross-party explanation of the logic for change in the following areas:

- Wealthy old folk paying for their health and social care needs, preferably through mandated private health insurance on which the NHS could draw as its services are used, but which would also, gradually, enable more choice;

- Young people having an economically stable start to adult life: the fact that average student debt for those starting work from university is c. £45,000 is not acceptable, and we need to ensure that those from low-income/disadvantaged backgrounds have starter capital accounts and life skills training, preferably on an incentivised basis; and

- providing more targeted support for those in need once the pressure from provision of universal welfare is removed.

There are, of course, only a small number of issues which we could expect to be included within cross-party consensus, but these three surely warrant that treatment. As with all Mexican stand-offs, this means that some politicians will have to give way on cherished beliefs, but the country will thank them for it.

The Bennett Institute conference went on to discuss how the Civil Service could be reformed/re-imagined for the 21st century, and Jonathan Slater, whose 20 year career includes Justice, Defence, Education, the Cabinet Office and No. 10, provided a very frank description of the challenges it faces.

Not least among these is the deference which Civil Servants have to give to Ministers, whose perspective is invariably short-term. The Civil Service is often keenly aware of what needs to be done for the long-term interest of the country, but it is handicapped by the twists and turns of politics. As Harold Wilson said, ‘a week is a long time in politics’.

But the need to resolve the spiralling cost and desperate inefficiency of the NHS, together with the economic damage being inflicted on young adults, cannot be left to chance. We need a consensus to resolve the impasse, and we need that consensus to be reflected in the manifestos of at least the two main political parties for the coming election.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio