“No more aspiring to be an ISA millionaire, it would be £100k and out under this plan.”

This Is Money episode commentary

The Resolution Foundation set out a helpful analysis last Monday describing the challenge of inadequate UK personal savings, highlighted in The Sunday Times Money section. However, the impact of their proposals was wholly blunted and eclipsed by their attack on Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs), after which their report was named (‘ISA ISA Baby’). The ISA is possibly the most successful savings and investment incentive ever introduced in the United Kingdom, originating with Nigel Lawson's Personal Equity Plan launched in 1986.

In contrast to The Sunday Times, which chose to ignore this ill thought-out aspect of their analysis, Simon Lambert and his team at This is Money criticised their proposals to place harsh caps on high-value ISAs as ‘the most unpopular idea of the week’ and described the backlash, if they were ever implemented, as huge.

This is not the first time that The Resolution Foundation has missed the mark in its attempts to tackle the polarisation of wealth. This does need urgent action, both in the United Kingdom and overseas, and listeners will be aware that it also drives the SHARE project work now being done in Cambridge. A synopsis of that project’s initial propositions is set out in the Share Alliance website, and they are very different to The Resolution Foundation’s.

There are many issues which The Resolution Foundation fails to address in its analysis: the unwillingness of HM Treasury to hypothecate, the need to start earlier in life — with starter capital accounts and incentivised learning — and finish later, when people die rather than when they are living in retirement. They wholly miss the aspirational damage which would result from emasculating ISAs, and they ignore the fact that the annual ISA contribution limit was only lifted significantly six years ago because the Government had capped personal pensions, wanting people to use ISAs instead to save for their retirement.

So, in this commentary we pick up some of these issues in the hope that a more constructive approach can be taken to find a comprehensive and strategic approach to tackling wealth inequality: by ‘levelling-up’ individual assets rather than punishing individual success and thrift.

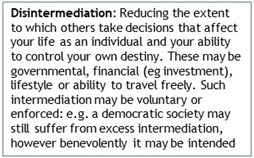

‘Tax and re-distribute’ is at the heart of The Resolution Foundation's idea: they clearly don't understand the importance of disintermediation, preferring to see Government pulling all the strings. This is Money draws attention to this Achilles’ Heel in that they can find no guarantee that additional taxation imposed on ISA investments would actually go to low-income savers. Having had my requests to HM Treasury for hypothecating at least part of the £7 billion per annum Inheritance Tax receipts for the benefit of disadvantaged young people turned down repeatedly over the years, I know that no such guarantee would be given.

‘Tax and re-distribute’ is at the heart of The Resolution Foundation's idea: they clearly don't understand the importance of disintermediation, preferring to see Government pulling all the strings. This is Money draws attention to this Achilles’ Heel in that they can find no guarantee that additional taxation imposed on ISA investments would actually go to low-income savers. Having had my requests to HM Treasury for hypothecating at least part of the £7 billion per annum Inheritance Tax receipts for the benefit of disadvantaged young people turned down repeatedly over the years, I know that no such guarantee would be given.

So, just linking the two main thrusts of The Resolution Foundation’s plan — more incentives for low-income savings, less tax relief for ISAs — is unrealistic. Inheritance Tax receipts exceed the total estimated tax foregone on ISAs by a long way, and this could be used to fuel ‘Help to Save’; but there wasn't even a mention of IHT in The Resolution Foundation's ‘ISA ISA Baby’ paper.

Apart from a panel describing Child Trust Funds, there was also no mention of existing starter capital accounts for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, and none whatsoever of the Junior ISA arrangements for young people in care, on which we focused last week. There was also no mention of financial education and the lack of a Financial Awareness GCSE, nor of the fact that only 25% of school leavers regard themselves as adequately prepared for adulthood in money terms. No wonder the take-up of ‘Help to Save’ is so low.

Their analysis begins by describing the very low use of this scheme in low-income households, notwithstanding the satisfaction expressed by those who have used it; but The Share Foundation (TSF) knows that you have to start earlier, at least during adolescence. TSF has also learned how effective incentivised learning is in order to transform attitudes — but there’s not a mention of this either in The Resolution Foundation's paper.

So, while we support their ideas for boosting ‘Help to Save’, they need to learn from current experience. For example, they should talk to The Share Foundation and HMRC about the challenge of building awareness of savings accounts, and gain an appreciation of the problems experienced in delivering automatically-opened HMRC-allocated accounts such as the 1.7 million Child Trust Funds opened for low-income families, where the great majority are unclaimed.

The Stocks & Shares ISA started life as the Personal Equity Plan (PEP) in 1986, and was intended to encourage a new era of direct share ownership alongside the massive programme of de-nationalisation, as the then Conservative government sought to reduce the domination of the state in key industries. Meanwhile the Single Company PEP was introduced to promote employee share ownership; in 1999 The Share Centre acquired over 90,000 such accounts from the then leading provider, Bradford & Bingley.

Personal Equity Plans became ISAs in 1999 and were joined by Cash ISAs which replaced the TESSA, or ‘Tax-Exempt Special Savings Account’.

Overall annual contribution limits were set at just £7,000 between 1999 and 2008; apart from an additional £3,000 allowed for over 50s, they were then increased at a relatively modest rate until 2014. An increase from £11,880 to £15,000 was introduced on 1st July 2014, and the further increase to £20,000 was introduced from tax year 2017/18 in order to encourage a shift towards using ISAs for retirement savings.

The Resolution Foundation would do well to study the motivations and logic for shaping these accounts over the past 40 years, before proposing a decimation of their appeal.

It’s worth noting that the key reason why ISAs have worked so well over the past 37 years (this includes the Personal Equity Plan era) is that they are incredibly simple:

- People make contributions out of their taxed income; there is no upfront relief;

- All ISAs are regulated by account providers so that they are professionally administered;

- There is no requirement for individuals to report ISAs in their tax returns; however, the HMRC receives annual reports from the providers to ensure that the rules are being followed.

Meanwhile ISA tax concessions remain modest: the ability to reclaim ‘Advance Corporation Tax’ on dividends was removed in 1999, and the restructuring of Capital Gains Tax in 2008 to disallow any recognition of cost inflation for long-term shareholdings found some compensation in the design of ISAs.

If The Resolution Foundation thinks that more tax should be raised from investment sources, punishing successful and thrifty British individual savers and investors is not the way to do it: this will simply destroy trust in a system which has been reliable for nearly four decades, and which has fostered a real aspiration to save.

They should respect the high regard for the simplicity and effectiveness of ISAs, and find incentive revenues for ‘Help to Save’ elsewhere: such as by persuading the Government to stop using Inheritance Tax receipts (drawn from private capital set aside for future generations) for current expenditure and apply them for inter-generational rebalancing, or by closing the tax loopholes in heavily-intermediated private equity — such as its ability to offset debt interest before tax.

And, if they want to re-balance across the generations, we recommend considering the proposals made to the Chancellor in our commentary ‘Health and the Economy’ on 17th October.

Hacking the guts out of ISAs is not the way forward.

Gavin Oldham OBE

Share Radio